Sustainability in infrastructure planning

Guiding sustainability outcomes in public water infrastructure decision making.

First published in Water e-Journal Vol 5 No 2 2020.

DOWNLOAD THE PAPER

Abstract

Sustainability is a lens for integrated analysis and decision making in public water infrastructure. Water projects are complex and form part of a wider network of services with linkages and inter-relationships across sectors.

As decisions on infrastructure priorities and projects have the opportunity to shape land use and impact on urban form, the decisions of today will have important, lasting implications for the future. Taking account of this complexity, it has now been recognised that investment analysis forming part of the business case needs to better embed sustainability considerations.

This paper discusses new approaches to investment appraisal that incorporate sustainability. Building Queensland’s updated business cases framework provides a recent example where sustainability now features more heavily in business case guidance.

For the water industry, the guidance provides an opportunity to better align investment decision making to meet broader organisational comitments to the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Moving beyond the project-level, there is an increasing opportunity for a programme approach that shifts the attention from efficiency and efficacy to broader sustainability outcomes that arise from a holistic, system-wide perspective with a focus on value creation.

This is especially relevant to the water sector where benefits are typically best realised through a system-based approach to infrastructure planning.

Introduction

Public infrastructure is central to sustainable development through its ability to bring both direct and indirect economic, social, and environmental benefits to society. Water infrastructure plays a critical role in shaping urban environments, contributing to the prosperity of communities across the globe with benefits across health, safety, productivity and environmental domains. It is critical to building resilience as part of climate change mitigation and adaption.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in 2015, present a refreshed international commitment to sustainability. The SDGs set a framework that may be applied at global, national and local levels for sustainability to remain relevant into the future and for sustainability to remain a key policy focus in the public arena (Le Blanc, 2015).

The international treaties committing to sustainable development continue to reflect on government policy at a global level. The SDGs also present the opportunity for governance systems to respond through both goal setting at an aspirational level and rule making that provides the behavioural prescriptions to allow goals to be achieved (Young, 2017).

Across Australia, the water sector is leading the way in sustainability management, whereby water businesses continue to face challenges associated with climate change, resource depletion and biodiversity impacts.

At the same time, water businesses understand the contribution of water to thriving, liveable and sustainable communities. A number of infrastructure organisations, including water utilities, have already made strong sustainability commitments in aligning their strategies and operations to the SDGs and by becoming signatories to the UN Global Compact.

Organisations that sign the Compact must commit to:

- Operate responsibly, in alignment with the UN Global Compact’s ten universal sustainability principles;

- Take actions that support the society around it;

- Commit to the effort from the organisation’s highest level, pushing sustainability deep into its DNA;

- Report annually on the organisation’s ongoing efforts; and

- Engage locally where the organisation has a presence.

Commitments by infrastructure providers to the SDGs demonstrate the renewed focus on sustainability and its role in addressing global problems. The challenge for infrastructure providers is to translate these sustainability commitments to project level decision making.

This paper builds on earlier research that sought to understand how sustainability considerations are integrated into decision making processes for infrastructure projects (Reidy, 2018) and provides an update on recent developments to incorporate sustainability in business case decision making, with particular reference to water investments.

Decision making framework for public infrastructure

Investment decision making refers to project planning and analysis undertaken prior to the scope of the project being defined and the budget being allocated. This analysis is typically presented in a business case document for a given project initiative whereby a number of delivery and operating options are analysed and a final investment solution is proposed (Silvius et al., 2013).

Decision making at the front-end of projects is critical to ensuring long-term project success through delivering benefits and creating value. Options identified and assessed would be expected to have different benefits, disbenefits and outcomes when assessed within a sustainability framework.

The failure of projects to meet policy objectives has been linked to the inadequacy of analysis and initial decision making in the initiating stage, where there is limited focus on strategic performance (relevance, effectiveness and sustainability) and greater focus on tactical performance (time, cost and quality performance) (Samset & Volden, 2015).

The rules and processes for business case development are critical in enabling opportunities to deliver sustainable and long-term community benefits, and create value across the social, environmental and economic domains.

Despite the range of tools to evaluate the impacts and benefits of infrastructure investments, there remain many unknowns relating to how infrastructure assets will perform and adapt into the future to meet challenges such as: resource scarcity and depletion; changes in the global economy and energy prices; an increasingly complex regulatory environment and community; and social issues (Marlow and Humphries, 2009).

An interconnecting system of rules, values and knowledge influence the decision making context, and may constrain future decisions as new issues emerge (Gorddard et al., 2016).

The planning and regulatory frameworks for infrastructure investments often fail to guide decision making to appropriately address emerging challenges such as climate change uncertainty (Ananda, 2014).

As infrastructure agencies seek new solutions to emerging challenges, institutional structures, settings and processes often act as barriers in justifying investments in new and innovative technologies that deliver multiple objectives (Brown & Farrelly, 2009).

Taking account of the long life-spans of infrastructure, there are numerous factors that add to uncertainty around how investments may perform and operate over time. Despite various approaches to dealing with uncertainty, decision making continues to focus on a single, pre-determined asset-based solution.

In the water sector, the Australian Academy of Technology and Engineering (ATSE, 2015) identified a need for new governance models to better manage urban stormwater in Australia and proposed more ‘robust’ appraisal models that acknowledge the complexity of integrated water management systems.

According to ATSE, the ‘present models are too narrow in scope and cannot assess the true value of investments made into green stormwater systems that provide high amenity value to our cities while delivering on basic water services’.

To date, much of the focus for applying sustainability to infrastructure investments has centred on tactical performance measures, including designing for resource efficiency and emissions reduction, and is typically incorporated into an already agreed functional design following front-end decision making linked to the business case (Haavaldsen et al., 2014).

However, the ability to apply sustainability initiatives in the design and operations stages may be limited where project scope is already determined and budget and timing parameters are already confirmed (Samset and Volden, 2015).

The application of sustainable concepts at the operational or tactical level is important and useful, however, such approaches do not necessarily lead to sustainable outcomes at the strategic level. There is a need to differentiate between doing the projects more sustainably and ‘choosing the more sustainable projects’, which is based on front-end decision making linked to the business case (Haavaldsen et al., 2014, p. 5).

Despite the growing involvement by the private sector in delivery, operation and maintenance of infrastructure services, these are typically public assets that are provided to benefit society and are subject to government oversight in planning and operation.

Infrastructure agencies operate within a wider system framed within an economic and political context, based on enabling legislation and government policy. Previous studies have shown systematic misalignment between stated government policy and decisions on project priorities and delivery (Young et al., 2012; Young and Grant, 2015).

Institutional design, framed in an economic and political context, is integral to achieving sustainability objectives in decision making (Ostrom, 2005). Policy making involves a range of policy actors operating within a rule-governed policy institution that exists at a particular time and place (Ostrom, 2010).

In the absence of clear policy and planning, decisions on infrastructure investments may become politicised, where outcomes and impacts are not well understood by either political proponents or the general community.

Regulatory agencies provide input to decision making based on legislative requirements in areas such as environment, health and or economics. Regulatory oversight provides a strong governance framework for decision making by public sector infrastructure providers, taking account of monopoly powers (Littlechild, 1988).

However, in practice, the role of the regulator may be based on incomplete understanding of the key issues and risks. In decision making relating to projects, regulators may not be aware of the full array of alternative investment opportunities available and regulatory decisions may not be cognisant of the interests of key user groups (Ananda, 2014).

In addition, the time frames that regulators adopt to assess proposals is limited, and may not take account of considerations of long-term intergenerational equity that strong sustainability assessment would require (Bond and Morrison-Saunders, 2011).

In a paper on economic regulation of urban water in Australia, Frontier Economics (2014) noted that regulatory oversight of capital investment decisions could more effectively assess the broader processes for approving investment decisions rather than scrutinising individual cost benefit studies.

This was demonstrated with evidence of sound business cases, evidence of engagement with customers to identify the outcomes they really value, and independent external scrutiny and audit. It took into account reviews already undertaken by multiple agencies responsible for project assurance.

In an institutional setting, decision making on infrastructure investments is often complex and involves a range of actors from across the infrastructure system. In current practice, the institutional settings influence how project appraisal is developed, interpreted and used in decision making. Institutional factors often determine the appraisal methodologies that are adopted, with subsequent impacts on sustainability outcomes.

Infrastructure sustainability rating tools and guidance

Sustainability considerations are increasingly being incorporated into the design, construction and operation phases of project lifecycle. Various rating tools have been developed for use in Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States, Canada, Sweden and Hong Kong to guide sustainability practice and to provide a framework to assess performance and benchmark across the infrastructure industry (Griffiths et al., 2015).

These tools include CEEQUAL, Envision, Greenroads, and the Infrastructure Sustainability (IS) Rating Tool developed by the Infrastructure Sustainability Council of Australia (ISCA). Research has shown that rating tools operate on a number of levels based on the formal use of tools leading to project certifications, informal uses that may include informing policy and management systems, and influencing practice in areas such as industry knowledge and driving wider industry change. (Griffiths et. al, 2018).

The overarching purpose of the IS Rating Tool is to push better sustainability outcomes in the infrastructure sector. A key consideration of this is that the IS Rating Tool does not reward “business as usual” practices. As such, the IS Rating Tool has evolved over time as industry practice has changed. Version 2.0 of the IS Rating, released in 2018, is the most recent iteration of the Rating Tool.

IS ratings can be sought for four phases of the project lifecycle: planning, design, as built and operations. To date, nine water sector projects have been formally assessed and verified through the scheme.

The Planning rating was released as part of Version 2 of the ISCA rating scheme and is in beta testing. Designed for projects from the strategic options assessment stage to the tender stage, the ISCA planning tool provides a framework for assessing the whole-of-life impacts of decisions made in the early stage of project development.

Methodology

This paper builds on PhD research by one of the authors entitled ‘Incorporating Sustainability in Investment Decision Making for Infrastructure Projects’, completed in 2018. The research focused on practice within the water sector.

A mixed methods (quantitative plus qualitative) study used an integrated inductive/deductive research approach to allow an explanatory model to be built. A quantitative study formed an initial stage, using a survey of industry experts to firstly test and refine a conceptual model. The survey provided insights into analysis techniques that are employed across the water industry.

In the second stage, thirteen interviews were conducted across Australia in late 2016 and 2017. The survey and interview data was analysed using a pragmatic/constructivist ‘research by designing’ approach that translates specialist knowledge into guidelines and models (Lenzholzer et al., 2013). This enquiry sought to build a deeper understanding of the context and policy setting of current practice and the difficulties in applying sustainability in a regulated sector.

Taking account of the unique characteristics of infrastructure and the public good that water investments may provide, a model was developed that is multi-layered, whereby projects align with broader strategic directions, whilst recognising that underpinning analysis should ensure robust and transparent project appraisal.

Benefits assessment for infrastructure investments should align with broader policy directions and include considerations of benefit for the wider community, beyond the boundaries of the infrastructure provider. A deeper understanding of value may be gained through working with a range of stakeholders including the end users of infrastructure.

Further to the research, a number of more recent developments are outlined whereby government agencies have now developed formal guidance to business case development. Frontier Economics has been working with several agencies to develop this guidance.

As the application of sustainability considerations within business case development is formalised and more broadly adopted, this paper addresses wider considerations in business case development.

Discussion: Business case guidance

Guidance for business case development has been a key role of infrastructure bodies across Australia. At the national level, Infrastructure Australia is tasked with the evaluation of infrastructure proposals that are nationally significant and, amongst other responsibilities, must develop a methodology that allows proposals to be compared.

At a state level, various infrastructure agencies or state agencies regularly provide updated guidance for business case development where those agencies provide regulatory oversight of infrastructure proposals that are deemed significant at a state level.

In this paper, sustainability refers to an integrated framework that reflects the interdependence of the economic, social, and ecological domains of sustainability and the complexity in managing these domains in a systematic way (Haas et al., 2017).

Prior to focussing on how broader sustainability goals may be incorporated in the business case guidance, it is worthwhile clarifying the high-level content of a business case. In simple terms, a business case can be broken down into five distinct steps:

- Starting from a problem

- Considering a broad range of potential solutions and narrowing them down to a short list of project options

- Conducting a robust assessment on the project options centred on cost-benefit analysis

- Selecting a preferred project option

- Being clear on the deliverability and affordability of the preferred project option.

In order to navigate these steps in a meaningful way, the process needs to be holistic and multi-disciplinary. This is particularly true for water projects. Therefore, a good business case should include the input of planners, engineers, environmental, social and economics specialists. This should ensure a well-rounded project is developed and help shape better investments using public money.

The ‘five case business case’ methodology, first developed as part of the Green Book guidance in the UK by HM Treasury, is often thought of as a best practice approach. However, this observation is more based on the logical flow and structure to this business case methodology rather than necessarily the breath of scope.

Infrastructure Australia’s paper on Reforming Urban Water notes the risks of climate change for the urban water sector and recommends that pricing decisions should drive efficiency, sustainability and innovation.

Infrastructure Australia’s Assessment Framework (2018) allows for sustainability to be incorporated into projects, however this is more of an opportunity than a requirement of the current guidance. It is currently in the process of being refreshed and this may bolster its sustainability and resilience requirements.

Building Queenland is the Queensland Government’s infrastructure advisory body, providing independent expert advice to support the government in making infrastructure decisions. Building Queensland’s updated business case guidance provides a recent example where sustainability now features more heavily in business case guidance.

As postulated above, for a business case to best harness the skills of a broad range of specialists, it follows that the scope of a business case should also be broad. In this regard the Building Queensland business case framework, first launched in 2016, includes broader areas of analysis including sustainability assessment, public interest considerations and an affordability analysis.

An updated Building Queensland business case framework was launched in 2020 (Building Queensland, 2020). A key change was the inclusion of more specific requirements for a sustainability assessment. The updated guidance recommends the use of ISCA’s IS Planning rating tool as a framework for the sustainability assessment element of an infrastructure business case.

Aligning the Building Queensland business case framework with the IS Planning rating is logical. The IS Planning rating tool is structured around the quadruple bottom line (governance, environmental, social and economic), which fits with Building Queensland’s business case approach. Embedding this sustainability assessment into the business case framework underlines the importance of including sustainability expertise in the business case development process.

As infrastructure investments are typically locked in for multiple generations, it is critical for governments to embed sustainability and indeed, resilience, into infrastructure planning and investment. The logic here is relatively simple. For this timeframe, climate change is a key driver, creating risk and uncertainty.

There are two logical implications here. First, new infrastructure should be looking to lessen its contribution to climate change – this is the sustainability angle. Second, the infrastructure should, as far as is possible, be sensitive to the natural hazards posed by climate change over the life of the asset – this is the resilience angle.

Business cases which take a clear and robust approach to sustainability and resilience are increasingly being sought by government and their treasuries.

Following is a brief discussion on further considerations in best practice investment appraisal.

A programme approach

Bell and Morse (2012) identified a preference by decision makers for a project-centric approach to infrastructure investments where funders are usually constrained by financial resources.

In a project context, clear objectives around timeframes, funds spent and quality may be set, against which a narrow perspective of performance may be measured. However, at a project level, optimal sustainability outcomes may be difficult to achieve. Projects are often contained within a limited geographical or jurisdictional area, but cannot address problems beyond those boundaries.

Infrastructure serves as a complex ‘system of systems’ with cross-sectoral interdependencies and multiple values that may change over time (Rosenberg et al., 2014, p.3).

As an example, integrated water projects present opportunities to provide multiple benefits ranging from water quality improvements, flood protection, and the provision of alternative water sources. These may go beyond jurisdictional boundaries and organisational management functions.

In order to more effectively solve these problems or opportunities, analysis may require an approach that considers wider benefits to communities, or programme level responses.

A programme approach takes a view beyond project-level outputs focused on efficiency and efficacy to broader outcomes that that may provide a holistic, system-wide perspective with a focus on value creation that aligns with sustainability objectives.

A systems-based approach based on programme management principles provides the opportunity for communities to define visions of sustainability and the pathways required to achieve sustainability outcomes (Bond and Morrison-Saunders, 2011).

The former UK Office of Government and Commerce (OGC) developed a suite of best practice guidance for project, programme and service management in the public with formal programme-level guidance provided by Managing Successful Programmes (MSP).

MSP is an international standard for programme management, and defines a programme as ‘a temporary, flexible organisation created to coordinate, direct and oversee the implementation of a set of related projects and activities in order to deliver outcomes and benefits related to the organisation’s strategic objectives’.

Whilst not specifically addressing sustainability, MSP provides the opportunity to develop broader responses to infrastructure problems through a focus on strategic performance and the delivery of wider benefits.

For business cases, guidance has tended to focus on projects rather than programmes. An exception to this has been New Zealand where a programme business case is a distinct stage within a wider framework with specific subsequent stages for individual initiatives or projects within the overarching programme (The Treasury, 2020). This approach strikes a balance between system thinking and an appropriate level of rigour being applied to key investments within a programme.

In Australia, the process is less clear. Victorian guidance (Department of Treasury and Finance, 2019) does suggest that a programme submission could be appropriate for a business case. More specifically, guidance proposes that, where appopriate, the Victorian Treasury’s preliminary business case template can be used for programmes.

The latest Building Queensland business case framework (Building Queensland, 2020) encourages consideration of programme business cases, though again it proposes that they comply with their project guidance.

Whilst this recognition of programmes within the business case framework is encouraging, the application of a framework intended for projects can be challenging. For example, developing and packaging a preferred programme of works may be better suited to being underpinned by stakeholder participation rather than following a multi-criteria analysis and cost-benefit analysis process as requried in project business case guidelines.

Participation

Previous research has identified the importance of participation by stakeholders, including end users, in the development of the business case (Reidy, 2018). Participation refers to collaborative processes of working with multiple stakeholders to build knowledge, develop trust and understanding, and manage uncertainty in decision making.

Participation in infrastructure decision making looks beyond participation models within political systems such as voting, lobbying and protesting, and instead looks at deliberative processes that allow the considered examination of the technical, environmental and social aspects of a given initiative.

This takes planning and analysis beyond the domain of engineers, technical specialists or economists employed by infrastructure providers, and broadens the assessment to take account of local knowledge that may not be formally documented.

For infrastructure providers, participation activities are aligned with a sustainability approach in the delivery of major initiatives, and address Goal 17 of the UN SDGs (Partnerships).

The benefits of participation in decision making include:

- Helping to define complex problems and find non-traditional pathways that may not be apparent through top-down approaches;

- Drawing on a wider range of expertise and practical experience of those working in the field;

- Improving the quality of assessment based on the understanding of values, interests and concerns of participants. This may include a greater understanding of indigenous knowledge and indigenous concepts of ‘country’;

- Creating greater legitimacy of decisions where those who are interested and involved understand the trade-offs that need to be made, see decisions as fair, competent and abiding with laws and regulations;

- Building the capacity of those involved in decision making in areas of communication, technical information and mediation, as well as future decision making;

- Building trust between participants; and

- Mobilising potential project champions, sponsors, donors and funders (from National Research Council, 2008; Jackson et al., 2012; Head, 2011).

Participation in front-end decision making need not be a challenging process for infrastructure providers, or one that takes analysis beyond more traditional top-down approaches. Increasingly, regulatory obligations require water authorities to engage with communities in planning or pricing decisions.

An understanding that participation involving representatives of the wider community or stakeholder groups is critical in a sustainable framework. In practice, participation processes are difficult. Two key questions are critical to the design of participatory processes:

- Who should participate in decision making?

- How should the process be conducted?

A collaborative approach to decision making acknowledges the limitations of political representatives or executive staff to fully explore the issues and opportunities available in infrastructure appraisal.

Stakeholder engagement typically involves those with more formal roles in government or representative organisations, and community engagement refers to broader engagement with the general public.

Recruitment methodologies may vary and the selection of participants and their degree of influence are critical issues in participatory design. The choice of participants must be complemented by considerations of how the participants come together and how they make decisions.

The design of collaborative processes requires the consideration of a range of factors including the nature of the organisation that is conducting the process and the attributes of the group that is being engaged. The collaborative design process may involve co-design of the approach with citizens that may also address the variety of goals and expectations of the process.

A broad participation framework is central to a sustainability model and should be integrated through all stages of the decision process.

Capability and leadership

The adoption of a sustainability assessment framework requires a shift from capability focused on technical expertise alone to one that involves social insight, environmental knowledge, economic analysis, as well as technical knowledge that is grounded in an understanding of a range of infrastructure solutions, including options other than infrastructure.

Key competencies required for business case development that is focused on sustainable outcomes include: critical thinking and the ability to identify the wider context of problems; the ability to lead and direct a multi-disciplinary team or work with multiple agencies; negotiation capabilities; and the ability and drive to develop complex concepts through to implementation.

Further characteristics identified in other studies include: systems understanding, emotional intelligence, values orientation, compelling vision, inclusive style, innovative approach and a long term perspective (Visser & Courtice, 2011).

These competencies are not typically learnt through tertiary studies, and it may be argued that technical training alone does not provide the skills to deal with non-routine problems and analysis of matters that may have impacts relating to deeply held values.

In addressing sustainability in business case development, new approaches are needed to incorporate concepts of integrated assessment, participative processes and dealing with values and trade-offs.

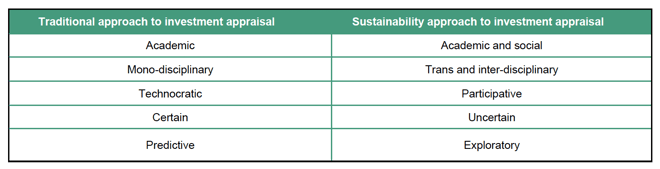

Table 1 illustrates the shift that is required to move from a traditional/technocratic approach to a sustainability approach in investment appraisal.

Conclusion

In order to address the challenges of planning in the face of sustainability pressures, investment appraisal must focus on the effectiveness of projects and programmes that align with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Water utilities have the opportunity to play a leadership role in taking forward a sustainability agenda for investment appraisal.

A number key challenges remain for sustainability appraisal. As regulated businesses, water utilities are often required to justify investments to a number of regulatory bodies. Each of these agencies may have different frameworks and requirements for business case submissions.

Frontier Economics has previously noted that regulatory oversight of capital investment decisions could more effectively assess the broader processes for approving investment rather than scrutinising individual cost benefit studies.

Moving beyond the project-level, there is an increasing opportunity for a programme approach that moves beyond considerations of efficiency and efficacy to broader sustainability outcomes that arise from a holistic, system-wide perspective with a focus on value creation.

This is especially relevant to the water sector where benefits are typically best realised through a system-based approach to infrastructure planning.

The opportunity exists to provide further guidance for sustainability appraisal within programme-level business cases and this may be a further step forward in better framing integrated, whole-of-system responses to sustainability in the formal business case development process.

About the authors

Angela Reidy | Angela Reidy is a Principal of Inxure Consulting, a Melbourne-based company providing advisory services on project and programme assurance in the infrastructure sector. With qualifications in civil engineering and business management, Angela has worked across the public and private sectors for 35 years, with a focus on front-end decision making and assurance for major projects. Throughout her career, Angela has been involved in projects with a range of environmental and social challenges including works in coastal zones and water management, as well as transport and urban development projects.

Ben Mason | Ben Mason is an Economist at Frontier Economics, an Australian consulting firm who provide economic advice across infrastructure sectors. Ben has led and managed economic analyses and business cases for a range of major infrastructure projects across the world. He has also developed a number of guidance documents including the economic theme within Version 2 of ISCA’s IS Rating Tool and Guidelines for Resilience in Infrastructure Planning for NSW Treasury.

References

Ananda, J., 2014. Institutional reforms to enhance urban water infrastructure with climate change uncertainty. Economic Papers: A journal of applied economics and policy 33, 123–136.

Bond, A.J., Morrison-Saunders, A., 2010. Re-evaluating Sustainability Assessment: Aligning the vision and the practice. Environmental Impact Assessment Review

31, 1–7.

Brown, A., Robertson, M., 2014. Economic evaluation of systems of infrastructure provision:concepts, approaches, methods (ibuild/Leeds Report). University of Leeds.

Brown, R.R., Farrelly, M.A., 2009. Delivering sustainable urban water management: a review of the hurdles we face. Water science and technology 59, 839.

Building Queensland, 2020. Stage 3 Detailed Business Case- Business Case Development Framework Release 3, https://buildingqueensland.qld.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Stage-3-Detailed-Business-Case.pdf (accessed 30/04/2020).

Department of Treasury and Finance, 2019. Investment Lifecycle and High Value High Risk Guidelines: Business Case, https://www.dtf.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/Investment%20Lifecycle%20and%20High%20Value%20High%20Risk%20Guidelines%20-%20Business%20Case%202019.DOCX (accessed 03/05/2020).

Frontier Economics, 2014. Improving economic regulation of urban water (A report prepared for the Australian Water Services Association). Australia.

Gosling, J.P., Pearman, A., 2014. Decision making under uncertainty: methods to value systemic resilience and passive provision. iBUILD/Leeds Report 43.

Griffiths, K., Boyle, C., & Henning, T. F., 2018. Beyond the certification badge—How infrastructure sustainability rating tools impact on individual, organizational, and industry practice. Sustainability, 10(4), 1038.

Haas, P. M. & Stevens, C., (2017). Ideas, Beliefs, and Policy Linkages: Lessons from Food, Energy and Water Policy in Governing through Goals (pp. 137–164). MIT Press.

Haavaldsen, T., Lædre, O., Volden, G.H., Lohne, J., 2014. On the concept of sustainability – assessing the sustainability of large public infrastructure investment projects. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 7, 2–12.

HM Treasury, 2018. Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/685903/The_Green_Book.pdf (accessed 30/04/2020).

Infrastructure Australia, 2018. Assessment Framework (For initiatives and projects to be included in the Infrastructure Priority List), https://www.infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/publications/assessment-framework-initiatives-and-projects (accessed 10/06/2020).

Jackson, S., 2006. Compartmentalising culture: the articulation and consideration of Indigenous values in water resource management. Australian Geographer 37, 19–31.

Jenner, S., 2010. Transforming Government and Public Services : Realising Benefits through Project Portfolio Management. Ashgate Publishing Ltd, Farnham.

Keeys, L.A., Huemann, M., 2017. Project benefits co-creation: Shaping sustainable development benefits. International Journal of Project Management.

Kemp, R. & Martens, P., 2007. Sustainable development: how to manage something that is subjective and never can be achieved? Sustainability: Science, Practice, & Policy 3.

Le Blanc, D., 2015. Towards Integration at Last? The Sustainable Development Goals as a Network of Targets. Sustainable Development 23, 176–187.

Lenzholzer, S., Duchhart, I., Koh, J., 2013. ‘Research through designing’ in landscape architecture. Landscape and Urban Planning 113, 120–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2013.02.003

Littlechild, S., 1988. Economic Regulation Of Privatised Water Authorities And Some Further Reflections. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 4, 40–68.

Marlow, D., Humphries, R., 2009. Sustainability within the Australian water industry: an operational definition. Water (Melbourne) 36, 118.

National Research Council, 2008. Public participation in environmental assessment and decision making. National Academies Press.

Ostrom, E., 2005. Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press Princeton, New Jersey.

Ostrom, E., 2010. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. The American Economic Review, 100(3), 641–672.

Reidy, A. D., 2018. Incorporating sustainability in investment decision making for infrastructure projects (Doctoral dissertation, Queensland University of Technology) https://eprints.qut.edu.au/119192/2/Angela_Reidy_Thesis.pdf (accessed 04/05/2020).

Reidy, A., Kumar, A., Kajewski, S., 2014. Sustainability in Infrastructure Investment- Building the Business Case, in: Practical Responses to Climate Change. Presented at the Engineers Australia Convention 2014, Engineers Australia, Melbourne, Australia.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin III, F.S., Lambin, E., Lenton, T., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schellnhuber, H.J., 2009. Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and society 14.

Rosenberg, G., Carhart, N., Edkins, A. J., & Ward, J. (2014). Development of a Proposed Interdependency Planning and Management Framework. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1455020/ (accessed 10/06/2020).

Samset, K., Volden, G.H., 2015. Front-end definition of projects: Ten paradoxes and some reflections regarding project management and project governance. International Journal of Project Management 34(2), 297-313.

Silvius, G., Tharp, J., Weninger, C., Huemann, M., 2013. Project Initiation: Investment Analysis for Sustainable Development, in: Sustainability Integration for Effective Project Management. IGI Publishing, Hershey PA USA.

Steffen, W., Grinevald, J., Crutzen, P., McNeill, J., 2011. The Anthropocene: conceptual and historical perspectives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 369, 842–867.

The Treasury, 2020. Progamme Business Case. Retrieved from https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/state-sector-leadership/investment-management/better-business-cases-bbc/bbc-guidance/programme-business-case

Visser, W., & Courtice, P., 2011. Sustainability leadership: Linking theory and practice. Available at SSRN 1947221.

Young, O.R., 2017. Conceptualization:, in: Governing through Goals, Sustainable Development Goals as Governance Innovation. MIT Press, pp. 31–52.

Young, R., Grant, J., 2015. Is strategy implemented by projects? Disturbing evidence in the State of NSW. International Journal of Project Management 33, 15–28.

Young, R., Young, M., Jordan, E., O’Connor, P., 2012. Is strategy being implemented through projects? Contrary evidence from a leader in New Public Management. International Journal of Project Management 30, 887–900.