Advanced monitoring of chemicals in water systems: Insights from an Australian pesticide case study

Abstract

The increasing prevalence of micropollutants, including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and personal care products, poses risks to aquatic ecosystems and human health. Traditional monitoring methods are ineffective in detecting these contaminants due to their typically low concentrations and intermittent occurrences. This study presents an integrated framework combining chemical prioritisation, passive sampling technologies, and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) to address these challenges. Using pesticides in the Greater Melbourne area as a case study, the framework demonstrates a streamlined approach for identifying, monitoring, and assessing chemicals of concern. Passive samplers, including Chemcatcher® and (Polar Organic Chemical Integrative Sampler) POCIS, deployed at 32 sites, yielded significant detection of pesticides, with 4 novel fungicides identified across multiple seasons. Specific, efficient analytical methods were then developed to quantify these at environmental concentrations. The hybrid use of passive and grab sampling, coupled with advanced analytical methodologies, provided comprehensive insights into contamination profiles, seasonal trends, and potential risks. This adaptable framework offers a scalable solution for monitoring diverse micropollutants in water systems, supporting informed water management and regulatory decisions to safeguard ecological and human health.

Introduction

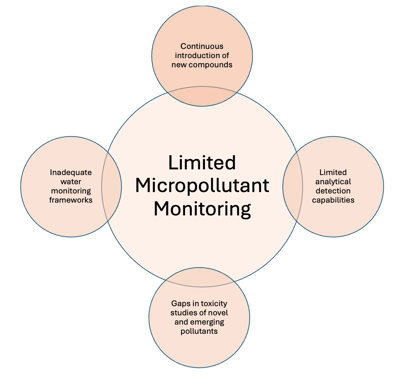

The growing presence of micropollutants (also referred to as chemicals of concern, and priority substances) in water systems is of current global concern (Mutzner et al., 2022; Narwal et al., 2023), particularly in Australia. (Allinson et al., 2023). These contaminants, including pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and pesticides, are increasingly detected in aquatic environments, posing risks to both environmental and human health. Monitoring these pollutants can be complex (Figure 1) due to their typical occurrence at low concentrations and as complex mixtures leading to uncertainties in accurate and efficient sampling and chemical analysis. Conventional monitoring methods, such as grab sampling and targeted analysis, can fall short in providing comprehensive detection, are labour-intensive, and incur high costs, limiting their effectiveness for large-scale or long-term applications.

Figure 1: Overview of current issues around limitations in micropollutant monitoring in water systems

To overcome these limitations, advanced technologies are emerging as transformative tools for water quality monitoring. Passive sampling offers cost-effective, long-term monitoring capabilities, enabling the detection of low-concentration pollutants without frequent sampling. Similarly, advancements in analytical methods, such as High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS), facilitate suspect screening and non-targeted analysis (NTA), improve detection limits, and enable expanded pollutant profiles, including previously undetected contaminants. Coupled with contaminant shortlisting frameworks (Serasinghe et al., 2022) these innovations enable the integration of monitoring data for predictive modelling to inform water management strategies.

Australia faces challenges due to its variable water quality, driven by harsh and changing weather conditions, urbanisation, agriculture, and mining in various parts of the continent. The limited regulatory frameworks for micropollutants and fragmented monitoring efforts highlight the need to adopt these advanced technologies for their mainstream detection and identification in aquatic systems. By leveraging advanced and efficient sampling, Australia can enhance its monitoring capabilities, develop tailored pollution mitigation strategies, and strengthen regulatory guidelines to support sustainable water management in the future.

Methodology

Understanding micropollutant contamination in water systems is crucial for effective water management and regulation. Variations in water systems’ physical, chemical, and biological properties influence micropollutant behaviour, complicating the development of measures to protect ecological values and human health.

We introduce a novel approach that integrates advanced technologies to prioritise and customise micropollutant screening for specific regions. Using pesticides as an example, the method focuses on surface water systems and the protection of non-target aquatic organisms. The case study is in the Greater Melbourne area, Victoria, Australia.

Stage 1: Chemical risk assessment.

A simplified, novel and robust approach for shortlisting and prioritising pesticides for inclusion in pesticide monitoring programs for specific regions was developed (Serasinghe et al., 2022). The methodology involves several steps: and identifying pesticides registered in significant regional land uses. The determination of registered and approved chemicals (in this case, pesticides) was conducted using the online PubCRIS database (Australian Government), an up-to-date resource for information on all registered pesticides within Australia. The second step involves the establishment of a priority list by filtering pesticides that are potentially toxic to human health and non-target aquatic organisms that are not routinely screened by local analytical laboratories. The National The National Association of Testing Authorities (NATA), Australia, accredits laboratories that test for chemical residues using methods that meet the requirements of ISO/IEC 17025 (NATA, 2021; Serasinghe et al., 2022). The NATA (Australia) database was used to identify Australian accredited laboratories and the pesticides they test for in aquatic systems. This information served as a filter to assess the routine monitoring capabilities of laboratories for pesticides in Australia. Newly introduced chemicals are subject to in-silico toxicity assessment for risk to human health and ecological values prior to entering the market. Global Harmonized System (GHS) classifications and/ or in silico toxicity thresholds from online toxicity databases such as the Pesticide Properties Database (PPDB) and its sister databases, including the Bio-Pesticide and Veterinary Substances Databases were utilised as part of the prioritisation method to further shortlist compounds (Lewis et al., 2016).

For Pesticides prioritisation for routine monitoring, it important to understand what type of agricultural commodities are primarily used within the region. This can have a direct impact on the volume and types of pesticides used. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) database on major grossing commodities within the region was assessed to identify likely pesticide use profiles associated with such commodities (ABS, 2020).

This short-listing methodology allows identification of pesticides that are registered for use, potentially toxic and not routinely screened for in water systems. Future updates could also include key pesticide transformation products of high toxicity to non-target aquatic organisms.

Stage 2: Broad scale sampling and chemical screening

Passive Sampling

Monitoring of micropollutants within water systems is further challenged by their variability in occurrence and typically trace concentrations. Traditional water sampling techniques, in particular grab (also known as spot) sampling, is commonly employed in micropollutant monitoring. These techniques have limitations, such as the inability to detect intermittently occurring pollution events, and to capture the presence of non-routinely monitored compounds due to their typically ultra-trace level concentrations. In contrast, passive sampling technology, exemplified by devices like Chemcatcher® Empore™ disk-based samplers, and Polar Organic Chemical Integrated Sampler (POCIS), offer a valuable alternative in water monitoring (Ahrens et al., 2016). Through the accumulation of contaminants passively over an extended time period and the capacity to provide time-weighted average water concentrations (TWAC), passive sampling is effective in addressing the limitations associated with grab water sampling for micropollutants within surface water monitoring.

To demonstrate the practical application of passive sampling in the field, two devices Chemcatcher® (SDB-XC) and POCIS were selected for our case study and deployed at 32 surface water sites across the Greater Melbourne region (GMA), encompassing areas with diverse and distinct land use activities (Figure 2). These samplers were chosen specifically for their ability to detect pesticides, a key class of micropollutants targeted in this study, due to their capacity to sequester a wide range of polar and semi-polar organic compounds over time. It is important to note, however, that the suitability of passive sampling depends on the chemical properties of the contaminants of interest. While passive samplers like Chemcatcher® and POCIS are well-suited for organic micropollutants, the monitoring of trace metals such as lead (Pb) cadmium (Cd), or zinc (Zn) typically requires alternative approaches such as sediment quality assessments, since these elements tend to partition into particulate matter rather than remain in the dissolved phase (Allinson et al., 2016).

These passive samplers and their receiving phases were selected based on the physiochemical properties of the chemicals namely – the short-listed pesticide list generated from stage 1. The physiochemical properties of those pesticides and the absorptive capabilities of the receiving phases of the passive samplers were reviewed based on empirical evidence to ensure and maximise the detection capabilities within the water systems.

Figure 2: Images of POCIS and Chemcatcher passive samplers in steel housing (left) and their field deployment (right)

Figure 2: Images of POCIS and Chemcatcher passive samplers in steel housing (left) and their field deployment (right)

Chemical analysis

Passive sampling was carried out between January and August 2021. The equipment used and detailed procedures for passive sampler deployments, extraction and instrumental analysis can be referred to at (Serasinghe et al., 2024a).

HRMS based Quadrupole Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (QToF MS), enables targeted screening to detect compounds with existing data, similar to conventional MS analysis (Serasinghe et al., 2024a). Additionally, it offers suspect screening based on molecular and structural data, helping identify potential contaminants in water systems and complementing the compounds shortlisted in Stage 1.

Using HRMS QToF analysis, an analytical screening library is a critical tool for suspect screening. In our study, we used our pesticide prioritisation method to shortlist suspect pesticides, which we then incorporated into our custom screening library to search for in our samples. Although online databases such as Norman, MassBank library for example (González-Gaya et al., 2021), containing thousands of known and registered compounds are available and can be used for broader screening purposes in non-target screenings, our approach specifically focused on suspect compounds identified in Stage 1.

By comparing mass spectra and chromatographic data from samples against tailored libraries using vendor-supplied screening software and manually verifying results through established hierarchical frameworks such as the Schymanski scale (Schymanski et al., 2014)or Best Practices for Non-Target Analysis (BP4NTA) (Peter et al., 2021), matches from suspect or non-target screening can be accurately identified and confirmed. This approach enhances detection confidence and enables fast, focused analysis of potential contaminants. In this case study, applied to the Greater Melbourne Area (GMA), Australia, passive sampler field extracts were analysed using LC-QToF-MS at the National Measurement Institute (NMI) laboratory in Melbourne. A suspect screening was conducted for 181 pesticides, which were shortlisted using the method outlined in the Stage 1: Chemical assessment for the GMA. Screening was carried out using the Waters UNIFI Screening Library (Waters, 2024). Compound specific details on the 181 pesticides are provided at Serasinghe et al. (2024a).

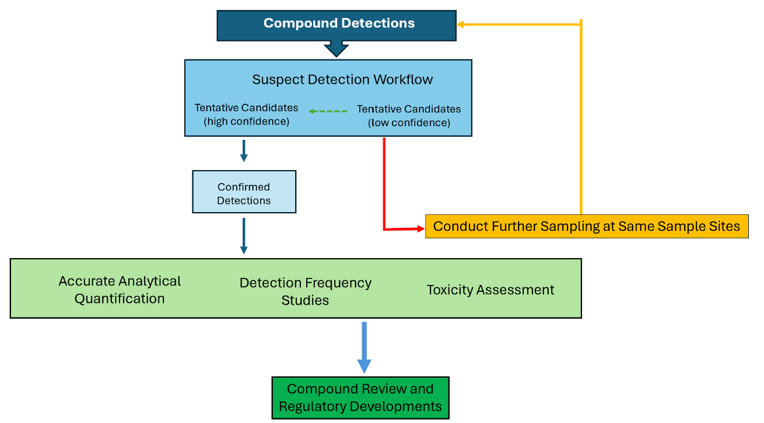

Stage 3: Tertiary workflow

Compound detections are reviewed and categorised into detection with high confidence and low confidence by adapting a standardised hierarchical system largely utilised globally for HRMS based chemical screening (Schymanski et al., 2014; Schymanski et al., 2015). Compounds with high detection confidence are selected for confirmation using their certified reference standards (CRM)s and be selected. further risk assessment if required (Figure 3). In the instances where CRMs may not be available, high confidence identifications can be supported through the use of a structurally analogous compound with similar fragmentation behaviour or by sourcing the standard from an internationally recognized provider such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2025).

Micropollutant presence in water systems can be influenced by seasonal changes and varied usage patterns of chemicals across different land uses in a region. Spatial and temporal monitoring of confirmed compounds can be utilised to assess detection frequency of micropollutants and identify key trends such as where concentrations can peak. Seasonal deployment of passive samplers could be utilised for this assessment.

While passive sampling provides a semi-quantitative assessment of the presence of compounds in water systems, accurate and sensitive quantification of these compounds at environmental levels can be challenging. To achieve this, intermittent grab water sampling can be employed to determine precise and environmentally relevant concentrations. In addition, efficient and sensitive analytical methodologies may need to be developed and validated in the laboratory for such quantification. The quantification results can then be used to supplement laboratory toxicity tests, helping to assess toxicity at measurable levels to protect various ecological values and human health.

For compounds with low detection confidence, further passive sampling at the initial sites may be necessary to verify whether initial detections were true or false positives to determine whether to proceed with the risk assessment.

Figure 3: Stage 3 tertiary workflow diagram illustrating suspect screening and tertiary workflow process

Results and discussion

Field application of pesticide prioritisation methodology

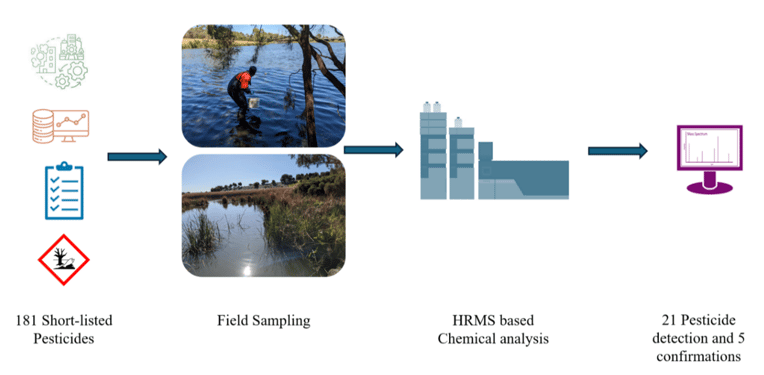

The simplified chemical prioritisation method by Serasinghe et al. (2022) applied to the GMA generated a list of 181 pesticides of potential concern likely to be locally used that may contaminate local surface waters. Thirty-two sites in Greater Melbourne were chosen for this validation experiment, given their agricultural significance and wide pesticide use. Employing passive sampling devices and suspect screening via Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (UPLC-Q-TOF) based MS, 21 potential pesticides were tentatively identified with high confidence under the utilised analytical workflow (Figure 4). Two confidence levels (1 and 2), based primarily on the classification system by Schymanski et al. (2014), were adapted as filters incorporating key analytical criteria (Serasinghe et al., 2024a). Detections meeting filter 1 criteria were selected for confirmation using CRMs. Both passive sampler types performed well under varying weather conditions, detecting at least one pesticide at 22 of 32 sampling sites. The Chemcatcher® variant had a higher percentage of detections compared to POCIS. The presence of 5 of the 21 detected pesticides was confirmed using certified reference standards, marking the first successful detection of these pesticides in Australian surface water systems (Serasinghe et al., 2024a).

Figure 4: Overview of stage 2 pesticide prioritisation and field application process and case study results

Understanding seasonal trends

Surface water pollution by pesticides can show seasonal and streamflow-related variation (Chow et al., 2020). Strong seasonal patterns in the usage of many agrochemicals is due to their seasonal use in crop growth and pest stress (Taylor et al., 2020). The timing and frequency of surveys is another important consideration for effective monitoring of pesticides. Surveys should occur when pesticides are most likely to be applied to maximise pesticide detection.

Using the suspect screening workflow and confirmation with CRMs (Serasinghe et al., 2024a), 5 pesticides were confirmed in surface waters across the GMA. These findings prompted further evaluation under stage 2 of the proposed framework. Three confirmed compounds (fluopyram, penthiopyrad, pydiflumetofen) were of a novel Succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHI) class of fungicides with the 4th (fluopicolide) a structurally similar fungicide with a different mode of action. A targeted seasonal trend investigation of these 4 novel fungicides was conducted using 2 types of passive samplers deployed for a period of 28 days. This analysis employed a targeted Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) analysis at 5 sites over 4 seasons within the GMA.

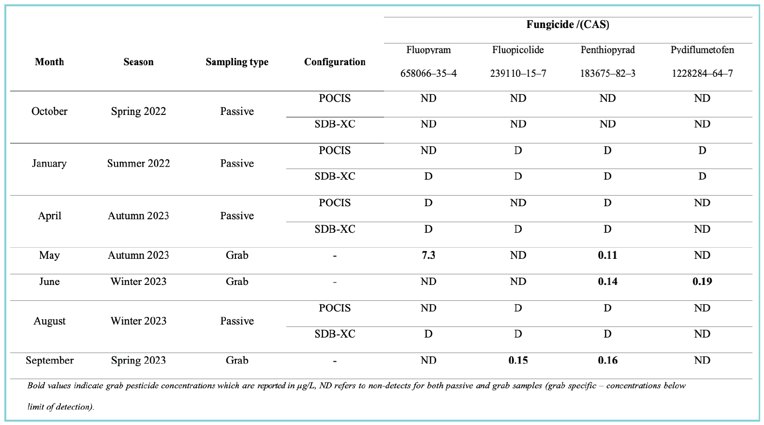

The 4 fungicides examined were consistently detected across five sampling sites during 3 of the 4 seasons: summer 2022, autumn 2023, and winter 2023. One site, in particular, showed the highest number of detections, especially in summer 2022 and the following seasons (Table 1). It is important to note that no pesticide detections were recorded during the spring of 2022. This was probably due to high rainfall occurring during their deployment (Bureau of Meteorology, 2022), that may have prevented fungicide applications.

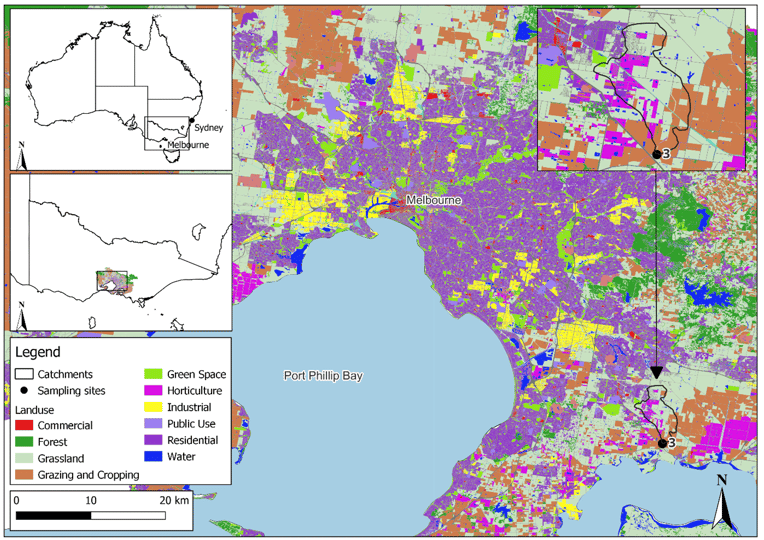

Quantification of newly detected pesticides

The consistent detection of 4 fungicides across the sampled sites using passive sampling, emphasized the persistence of some compounds. As part of the tertiary workflow and associated risk assessment, a validated analytical method was employed to reliably quantify the four fungicides at environmentally relevant levels (Serasinghe et al., 2024b). This methodology was applied to real grab water samples from one site collected over three months within the GMA. This site was chosen based on its intensive agricultural and residential land uses (Figure 5) and previous detection of these fungicides from stage 2 results. All 4 fungicides were detected at varying concentrations, with one, fluopyram, measured at a concentration significantly higher than previously reported in global surface water studies (Table 1). Further details on fungicide structures, standard sourcing, and key method validation parameters including detection limits and instrument performance are available in Serasinghe et al. (2024b).

Figure 5: Land use image of surface water sampling site (n = 1) for method application within the GMA, Victoria, Australia. Adapted from Serasinghe et al. (2024b)

Table 1: Pesticide detection summary of stage 3 and 4 implementations within the GMA

By providing both qualitative (passive sampling) and quantitative (grab water sampling), we were further able to demonstrate and suggest that a hybrid approach, combining passive sampling and grab water techniques, can generate a more extensive dataset on the occurrence of novel pesticides in regional surface water systems. In this case study, passive sampling was primarily used to provide presence/absence data, offering insight into the seasonal occurrence and potential persistence of target compounds. While our focus was on qualitative detection, it is important to note that both calibrated passive samplers (for deriving time-weighted average concentrations, TWACs) and grab water sampling can be used to obtain real-world quantitative concentrations, enabling more detailed environmental assessments where required. Through the monitoring studies conducted during this case study, the presence of 4 emerging fungicides were confirmed, consistently detected, and quantified with some at above trace levels seasonally (Serasinghe et al., 2024a; Serasinghe et al., 2024b). Recent data on the fungicides investigated have highlighted their moderate to high toxicities to non-target aquatic invertebrates and fish (Jin et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022) with several recent studies raising possible non-genotoxic carcinogenic effects on mammalian species indicative of potential risks to exposed humans (d’Hose et al., 2021; Duarte Hospital et al., 2023).

Considering the global scarcity of both detection and specific toxicity studies for these compounds, further toxicity testing at environmentally relevant concentrations would be the next step within this framework. Toxicity tests should involve assessment on individual fungicide exposure as well as in mixtures – considering the observed persistent presence of these fungicides both individually and in mixtures over several seasons.

Method applicability

Chemical prioritisation

The methodology and case study presented in this manuscript demonstrate a chemical prioritisation approach applied within Greater Melbourne Area, using passive sampling and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) to identify contaminants of concern in surface waters. This streamlined method is effective for prioritising emerging pesticides and can be extended to other micropollutants as well as other water systems, including potable, wastewater, and recycled water.

The initial stage involves prioritising contaminant classes, such as pharmaceuticals and industrial chemicals, using key regulatory databases. For pesticides, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) and PubCRIS databases provide registration and toxicity data (APVMA, 2017). This was a crucial initial step in integrating toxicity data and laboratory pesticide screening.

For industrial chemicals, the Australian Industrial Chemicals Introduction Scheme (AICIS) serves as the regulatory body for managing chemical introductions in Australia. (DHAC, 2023). AICIS employs risk-proportionate regulation across cosmetics, household goods, manufacturing, and agriculture. Like PubCRIS, the AICIS web database provides comprehensive data on industrial chemicals, including their Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) numbers, registration status, and assessments. It also includes toxicological and environmental impact summaries, offering a more detailed resource for industrial chemicals than PubCRIS, which could benefit from adopting similar features.

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) database is another valuable tool for prioritising micropollutants, particularly pharmaceuticals that may enter the environment through excretion, improper disposal, or manufacturing. The PBS database lists government-subsidized pharmaceuticals, making it a useful resource for identifying commonly prescribed drugs in Australia. As the database is regularly updated, it allows tracking new pharmaceuticals, which is essential for understanding potential risks to human and environmental health (DHAC, 2024).

These databases – PubCRIS, AICIS, and PBS – may enhance prioritisation efforts by offering critical data on chemical use, properties, and toxicity, supporting the development of suspect compound lists for further monitoring and analysis.

Sampling and chemical analysis

Micropollutants in water systems exhibit highly variable physicochemical properties, making reliable sampling challenging. Environmental and weather fluctuations further complicate detection, potentially underestimating pollution levels. The use of passive sampling as an updated alternative technology for water monitoring is currently seeing an upward trend.

This case study highlights the effectiveness of passive sampling for broad pesticide screening across multiple sites. Using two types of passive sampling devices (PSDs), pesticides were identified at 22 of 32 sites through suspect screening (stage 2). Four emerging fungicides were monitored across seasons in the GMA to assess their persistence in surface water over 4 sampling seasons (stage 3). Their efficacy has also been demonstrated in recent Australian studies, including estuaries (Jamal et al., 2024) and urban city streams (Allinson et al., 2023). Notably, Sydney Water’s pilot study (Sydney Water, 2024). marks a significant step toward the large-scale integration of passive sampling for micropollutant analysis. Globally, this trend is mirrored by increasing adoption of specialized PSDs for aquatic micropollutant monitoring, especially in waste and recycled water systems (Shiva et al., 2016; Gallen et al., 2019).

Selecting appropriate PSD types and receiving phases is essential, as micropollutants have diverse chemical properties such as polarity, solubility, and molecular size that affect their interactions with water systems. These interactions are further influenced by hydrological and physicochemical conditions, including water flow, temperature, and pH. To effectively capture a broad range of micropollutants, samplers must align with the target pollutants’ behaviour in specific water environments.

Detection results showed that Chemcatcher® outperformed POCIS in certain cases, particularly for SDHI fungicides. This may be attributed to the aforementioned factors or design limitations affecting absorption, as highlighted by prior studies (Pinasseau et al., 2019; Grodtke et al., 2021). While passive samplers provide Time-Weighted Average Concentrations (TWAC), calibration for emerging compounds lacks global standardization, making it difficult to determine accurate environmental concentrations (Garnier et al., 2020; Hawker et al., 2022). Consequently, this case study used qualitative results, to indicate the presence or absence of compounds investigated (Table 1).

Grab sampling provides accurate, quantifiable environmental concentrations, but relying solely on it lacks temporal representativeness, capturing only instantaneous data and potentially missing short-duration fluctuations when deployed infrequently (Garnier et al., 2020). Additionally, the analytical methodology must be sensitive enough to accurately identify concentrations at or above trace levels. Using a robust and optimized methodology, 4 fungicides were quantified in grab samples at trace and above trace levels. Comparing both sampling methods showed that a hybrid approach, combining passive sampling and grab water techniques, offers a more comprehensive dataset on fungicide occurrence in water systems.

Stage 2 results highlight the growing use of HRMS for micropollutant analysis in aquatic systems, enabling efficient screening of 181 pesticides across samples. Combining passive sampling with HRMS enhances the precision and effectiveness of pesticide monitoring.

While HRMS enables both targeted and non-targeted analysis, screening numerous chemicals without prior knowledge can be costly and lead to excessive data processing, making it less efficient and more resource intensive. In this case study, a suspect workflow using HRMS with the UNIFI platform facilitated efficient screening. However, selecting a priority list of micropollutants can be challenging, depending on factors such as pollutant type and the specific aquatic system. For example, the compounds targeted in potable water differ from those in wastewater or recycled water systems. Additional databases, like AICIS and PBS, can help refine the suspect list.

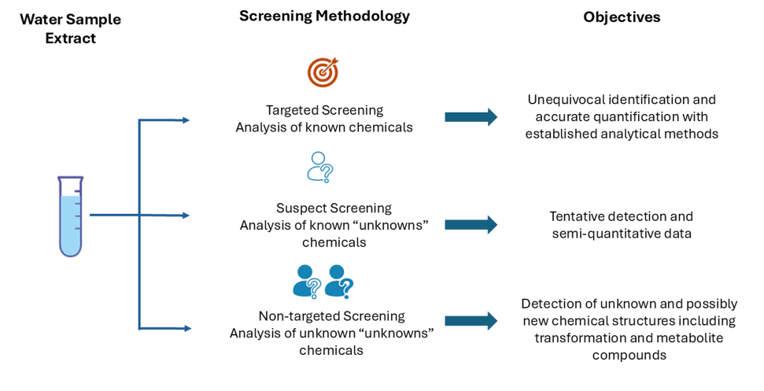

While suspect screening with platforms like UNIFI is effective for detecting hypothesized compounds, supplementing this with target screening for known pollutants and inclusion of a non-target screening for unknown contaminants would improve overall monitoring efforts (Figure 5). This combined approach ensures high precision for known compounds while offering broader coverage for unforeseen contaminants, optimising the overall risk assessment process.

Figure 6: Overview of HRMS based screeng methodologies and their objectives

Next steps

Identifying high-risk micropollutants in water systems is essential for assessing human health risks and protecting aquatic ecosystems and biodiversity. However, the detected concentration of a compound is critical in determining whether it is a contaminant of concern (CEC), as this directly influences its toxicity and impact on humans and non-target organisms.

An important initial step is conducting a thorough literature review, particularly of peer-reviewed studies on in vivo and in situ toxicity data from animal models, to understand the potential risks of contaminants at detected concentrations. For newly detected compounds with limited concentration-specific toxicity data, ecotoxicity tests on aquatic species and genotoxicity assessments can provide valuable insights into environmental impacts. Additionally, predicted toxicity models, such as quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models, can be used to evaluate the toxicity of both parent compounds and their metabolites (Burden et al., 2016).

For human health assessments, targeted approaches such as in vitro tests on cell lines, in vivo studies, and specialized assays (e.g., endocrine disruption tests) can be used for certain micropollutant classes to better understand potential health risks. Assessments should consider the specific use of the water, distinguishing between potable and wastewater to address relevant health impacts. Integrating concentration-specific toxicity data into existing risk assessment models will help develop regulations and guidelines, ensuring comprehensive protection across various water systems.

Further recommendations for proposed framework

This case study demonstrates that the proposed framework for identifying and detecting pesticides in surface waters can systematically address the challenges of monitoring emerging contaminants. The framework, initially applied to pesticides, can be adapted to monitor other micropollutants across various water systems, including surface, potable, wastewater, and recycled sources.

A key feature of the framework is the periodic prioritisation of contaminants, enabling continuous identification of novel compounds and ensuring monitoring efforts remain ahead of evolving products and land-use changes. Ongoing international collaborations offer opportunities to refine the framework, particularly for potable water sources with human health considerations.

Combining passive sampling and HRMS in suspect screening provides a potent, cost-effective model that can be customized for periodic monitoring. This approach efficiently captures contamination profiles, particularly during major weather events, and enables semi-quantitative concentration data. Integrating passive and grab water sampling techniques enhances the framework’s adaptability to emerging contaminants.

To improve micropollutant detection, advancing analytical capacities is crucial. Developing multi-residue methods and employing efficient extraction techniques, like QuEChERS, can reduce the challenges of labour-intensive chemical analyses, supporting the detection of low-level pesticide concentrations and enhancing monitoring in Australian water systems.

Conclusion

This study highlights the pressing need for advanced methodologies in monitoring and managing micropollutants such as pesticides in aquatic systems. By integrating a robust chemical prioritisation framework with innovative technologies such as passive sampling and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), the proposed approach offers an up-to-date solution for detecting and assessing emerging contaminants. The application of this framework within the GMA successfully identified and quantified novel fungicides showcasing its effectiveness in addressing the limitations of traditional monitoring methods.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Rhys Coleman (Melbourne Water) for providing this research opportunity through the Aquatic Pollution Prevention Partnership (A3P) between Melbourne Water and RMIT University, and his comments on the draft manuscript, and Dr Saman Buddhadasa for coordinating and supporting the collaboration between NMI and RMIT University. We would also like to thank the Aquatic Environmental Stress Research Group (AQUEST), RMIT for their assistance in field and laboratory work conducted during this research.

The Authors

Pulasthi holds a PhD in Applied Biology and Biotechnology (2024). He is currently working as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow within the Aquatic Environmental Stress Research Group (AQUEST) at RMIT University. His research focuses on detecting emerging pesticides in aquatic systems, leveraging novel sampling and analytical methods. With expertise in water quality and micropollutant analysis, he aims to influence policy and industry practices to mitigate environmental chemical exposure.

Hao Nguyen is the Technical Specialist and Operations Manager (Chemical Residues) at the National Measurement Institute. Specialising in high-resolution mass spectrometry, validation, quality assurance, and postgraduate training, she has developed methods addressing government priorities, including trace veterinary drugs in food and waterways. Her work extends to First Nations foods, environmental studies, and wildlife poisoning. Hao leads a team of 30 scientists and publishes research on veterinary drug residues, rodenticides, agrochemicals, and pharmaceuticals.

Saman is a Senior Manager of the Technical Development and Innovation - National Measurement Institute, Australia (NMIA). He has over 40 years of expertise in the development of methods including those for the assessment of contaminants and toxins in food and the environment. He coordinates collaborations between NMIA, universities and government and non-government organisations to address Australia’s current and future measurement needs.

Dayanthi is a leading ecotoxicologist and Head of the Ecotoxicology Research Group at RMIT University since 2004. Renowned for her work on aquatic pollution, she co-founded the AQUEST Research Group, has authored 180+ publications, and graduated 37+ PhD students. She has advised international and Australian government panels on toxicology and environmental impacts.

Vincent is the head of AQUEST at the RMIT University, specialises in aquatic pollution research and its impact on ecosystems. With over 40 years of experience, his work spans sediment toxicity, pesticide pollution, and biota as pollution indicators. Former CEO of CAPIM at the University of Melbourne, he has authored 140+ publications, aiding authorities in managing aquatic ecosystem health.

References

ABS, 2020. Value of Agricultural Commodities Produced, Australia, 2018-19.

Ahrens, L., Daneshvar, A., Lau, A.E., Kreuger, J., 2016. Characterization and Application of Passive Samplers for Monitoring of Pesticides in Water. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE, 54053.

Allinson, G., Allinson, M., Bui, A., Zhang, P., Croatto, G., Wightwick, A., Rose, G., Walters, R., 2016. Pesticide and trace metals in surface waters and sediments of rivers entering the Corner Inlet Marine National Park, Victoria, Australia. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 23, 5881-5891.

Allinson, M., Cassidy, M., Kadokami, K., Besley, C.H., 2023. In situ calibration of passive sampling methods for urban micropollutants using targeted multiresidue GC and LC screening systems. Chemosphere 311, 136997.

APVMA, 2017. Public Chemical Registration Information System - PUBCRIS. Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicine Authority,.

Burden, N., Maynard, S.K., Weltje, L., Wheeler, J.R., 2016. The utility of QSARs in predicting acute fish toxicity of pesticide metabolites: A retrospective validation approach. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 80, 241-246.

Bureau of Meteorology, 2022. Greater Melbourne in spring 2022: wettest spring since 1992, cold days.

Chow, R., Scheidegger, R., Doppler, T., Dietzel, A., Fenicia, F., Stamm, C., 2020. A review of long-term pesticide monitoring studies to assess surface water quality trends. Water Research X 9, 100064.

d’Hose, D., Isenborghs, P., Brusa, D., Jordan, B.F., Gallez, B., 2021. The Short-Term Exposure to SDHI Fungicides Boscalid and Bixafen Induces a Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Selective Human Cell Lines. Molecules 26.

DHAC, 2023. Industrial Chemicals Inventory.

DHAC, 2024. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).

Duarte Hospital, C., Tête, A., Debizet, K., Imler, J., Tomkiewicz-Raulet, C., Blanc, E.B., Barouki, R., Coumoul, X., Bortoli, S., 2023. SDHi fungicides: An example of mitotoxic pesticides targeting the succinate dehydrogenase complex. Environment International 180, 108219.

Gallen, C., Heffernan, A.L., Kaserzon, S., Dogruer, G., Samanipour, S., Gomez-Ramos, M.J., Mueller, J.F., 2019. Integrated chemical exposure assessment of coastal green turtle foraging grounds on the Great Barrier Reef. Science of The Total Environment 657, 401-409.

Garnier, A., Bancon-Montigny, C., Delpoux, S., Spinelli, S., Avezac, M., Gonzalez, C., 2020. Study of passive sampler calibration (Chemcatcher®) for environmental monitoring of organotin compounds: Matrix effect, concentration levels and laboratory vs in situ calibration. Talanta 219, 121316.

González-Gaya, B., Lopez-Herguedas, N., Santamaria, A., Mijangos, F., Etxebarria, N., Olivares, M., Prieto, A., Zuloaga, O., 2021. Suspect screening workflow comparison for the analysis of organic xenobiotics in environmental water samples. Chemosphere 274, 129964.

Grodtke, M., Paschke, A., Harzdorf, J., Krauss, M., Schüürmann, G., 2021. Calibration and field application of the Atlantic HLB Disk containing Chemcatcher® passive sampler – Quantitative monitoring of herbicides, other pesticides, and transformation products in German streams. Journal of Hazardous Materials 410, 124538.

Hawker, D.W., Clokey, J., Gorji, S.G., Verhagen, R., Kaserzon, S.L., 2022. Chapter 3 - Monitoring techniques–Grab and passive sampling. in: Dalu, T., Tavengwa, N.T. (Eds.). Emerging Freshwater Pollutants. Elsevier, pp. 25-48.

Jamal, E., Reichelt-Brushett, A., Gillmore, M., Pearson, B., Benkendorff, K., 2024. Pesticide occurrence in a subtropical estuary, Australia: Complementary sampling methods. Environmental Pollution 342, 123084.

Jin, L., Yun, G., Wei, M., Kaiyun, W., Hui, X., Jie, L., 2016. Acute toxicity of fluopicolide to 9 kinds of environmental organisms and its bioaccumulation in zebrafish. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 296-305.

Lewis, K.A., Tzilivakis, J., Warner, D.J., Green, A., 2016. An international database for pesticide risk assessments and management. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 22, 1050-1064.

Liu, Y., Zhang, W., Wang, Y., Liu, H., Zhang, S., Ji, X., Qiao, K., 2022. Oxidative stress, intestinal damage, and cell apoptosis: Toxicity induced by fluopyram in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chemosphere 286, 131830.

Mutzner, L., Furrer, V., Castebrunet, H., Dittmer, U., Fuchs, S., Gernjak, W., Gromaire, M.-C., Matzinger, A., Mikkelsen, P.S., Selbig, W.R., Vezzaro, L., 2022. A decade of monitoring micropollutants in urban wet-weather flows: What did we learn? Water Research 223, 118968.

Narwal, N., Katyal, D., Kataria, N., Rose, P.K., Warkar, S.G., Pugazhendhi, A., Ghotekar, S., Khoo, K.S., 2023. Emerging micropollutants in aquatic ecosystems and nanotechnology-based removal alternatives: A review. Chemosphere 341, 139945.

NATA, 2021. ISO/IEC 17025 Testing & Calibration. NATA.

National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2025. Standard Reference Materials (SRMs). U.S. Department of Commerce.

Peter, K.T., Phillips, A.L., Knolhoff, A.M., Gardinali, P.R., Manzano, C.A., Miller, K.E., Pristner, M., Sabourin, L., Sumarah, M.W., Warth, B., Sobus, J.R., 2021. Nontargeted Analysis Study Reporting Tool: A Framework to Improve Research Transparency and Reproducibility. Analytical Chemistry 93, 13870-13879.

Pinasseau, L., Wiest, L., Fildier, A., Volatier, L., Fones, G., Mills, G., Mermillod-Blondin, F., Vulliet, E., 2019. Use of passive sampling and high resolution mass spectrometry using a suspect screening approach to characterise emerging pollutants in contaminated groundwater and runoff. Science of The Total Environment 672.

Schymanski, E.L., Jeon, J., Gulde, R., Fenner, K., Ruff, M., Singer, H.P., Hollender, J., 2014. Identifying Small Molecules via High Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Communicating Confidence. Environmental Science & Technology 48, 2097-2098.

Schymanski, E.L., Singer, H.P., Slobodnik, J., Ipolyi, I.M., Oswald, P., Krauss, M., Schulze, T., Haglund, P., Letzel, T., Grosse, S., Thomaidis, N.S., Bletsou, A., Zwiener, C., Ibáñez, M., Portolés, T., de Boer, R., Reid, M.J., Onghena, M., Kunkel, U., Schulz, W., Guillon, A., Noyon, N., Leroy, G., Bados, P., Bogialli, S., Stipaničev, D., Rostkowski, P., Hollender, J., 2015. Non-target screening with high-resolution mass spectrometry: critical review using a collaborative trial on water analysis. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 407, 6237-6255.

Serasinghe, P., Nguyen, H.T.K., De Silva, T., Nugegoda, D., Pettigrove, V., 2022. A novel approach for tailoring pesticide screens for monitoring regional aquatic ecosystems. Environmental Advances 9, 100277.

Serasinghe, P., Nguyen, H.T.K., Hepburn, C., Nugegoda, D., Pettigrove, V., 2024a. Use of passive sampling and high-resolution mass spectrometry for screening emerging pesticides of concern within surface waters. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 13, 100408.

Serasinghe, P., Taleski, D., Nguyen, H.T.K., Nugegoda, D., Pettigrove, V., 2024b. Development and Validation of a Novel Method Using QuEChERS and UHPLC-MS-MS for the Determination of Multiple Emerging Fungicides in Surface Waters. Separations 11, 279.

Shiva, A.H., Bennett, W.W., Welsh, D.T., Teasdale, P.R., 2016. In situ evaluation of DGT techniques for measurement of trace metals in estuarine waters: a comparison of four binding layers with open and restricted diffusive layers. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts 18, 51-63.

Sydney Water, 2024. Wet Weather Overflow Monitoring Program Synthesis Report.

Taylor, A.C., Fones, G.R., Mills, G.A., 2020. Trends in the use of passive sampling for monitoring polar pesticides in water. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry 27, e00096.

Wang, Z., Tan, Y., Li, Y., Duan, J., Wu, Q., Li, R., Shi, H., Wang, M., 2022. Comprehensive study of pydiflumetofen in Danio rerio: Enantioselective insight into the toxic mechanism and fate. Environ Int 167, 107406.

Waters, 2024. Screening Platform Solution with UNIFI.