A Sustainable Brine and Salt Management Strategy: An Enabler for Climate Resilient Water Supplies For our Community

Abstract

Fast-growing population, decreased rainfall runoff and emerging industries requiring high-quality water are each leading to increased competition for sustainable water sources in Australia. Increasing demand for high quality water will lead to increased saline and complex wastes requiring brine management and disposal. Community expectation and environmental considerations will drive new brine management outcomes. In addition, emerging contaminants of concern including PFAS and microplastics require consideration in concentrated residuals produced. A crucial focus on brine and salt is required from the outset of projects, requiring comprehensive project and treatment planning. If brine is not managed adequately from the start, it leads to larger and more costly legacy issues to deal with, leading to higher ultimate costs for consumers.

The key considerations for inland brine management are fundamentally financial and require assessment of the cheapest (direct reuse or disposal of dilute brines) through to most expensive options (valorisation from concentrated brine or landfill of crystallised salt), minimising the proportion of brine requiring higher-technology and higher-cost treatment.

Seawater based systems often consider brine to be a hydrodynamic or ecological problem. For that circumstance, the dispersion of brine and impact upon the localised ecosystem are frequently the primary considerations.

Introduction

As Australia embarks upon becoming a future energy leader, as well as managing existing legacy issues, and drives to secure its anthropogenic water demand, the management of brine and salt adopts a much higher priority. There are several potential higher-quality water uses which will produce brine streams. Water for hydrogen has been touted as a potential way to capitalise on Australia’s renewable energy potential. The source of the water used to create green hydrogen will determine the required treatment to meet the high purity requirements and subsequently the importance of brine management. Another example includes increased implementation of advanced water treatment for water recycling including PRW. For PRW, additional brine treatment can be required to remove nutrients (Leslie, 2010) and/or PFAS prior to environmental discharge. There will also be increased water demand for cooling of industrial processes, electrolysers and data centres. Increased purity or recovery of product water increases the resulting concentration of process residual, often limiting the subsequent management options.

In addition, as the circular economy increases for purposes such as metal recovery and management of acid mine drainage, higher concentration and more complex saline waste streams will require to be managed. Brine has been a problem for stakeholders ever since the introduction of desalination for brackish water (BWRO) and seawater applications (SWRO). This is due to the salt balance that occurs from the processing of water for higher use application, driving purity requirements. This processing removes the salts from the raw water stream, concentrating them in the brine stream, leading to the requirement to manage them for environmental protection.

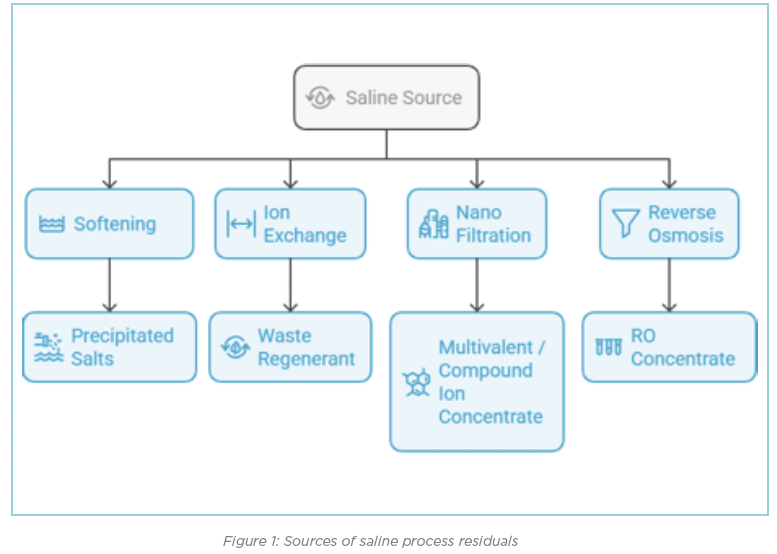

Brines can include a wide range of components including calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, fluoride, carbonate, bicarbonate, phosphate, nitrate, chloride, sulphate, silicate, dissolved metals and dissolved organics. Brine is generally thought of as the concentrate byproduct of RO, but other treatment processes can also generate a saline waste stream as presented in Figure 1.

For seawater desalination, brines are considered as water streams with a total dissolved solids (TDS) concentration of greater than 50,000 mg/L. However, water recycling and/or groundwater desalination could encounter saline residual streams of much lower salinity, e.g. 3,000 to 10,000 mg/L TDS.

Appropriate brine management is always location-, regulation- and climate-dependent, and requires consideration of all stakeholders. The management of brine will always be a major issue for inland operations, with these emerging applications for higher quality water and to implement higher drought resilience. The success of these projects will largely relate to funding, access to feed water, and community sentiment. Historical focus on just minimising the volume of brine will need to shift to a broader sustainability focus, with regulations for brine management requiring more active planning and management. This should be considered in relation to the United Nation Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) where brine management will play a role in achieving Clean Water and Sanitation (SDG 6), Affordable and Clean Energy (SDG 7), Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11) and Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12).

As a starting point, lessons learned from other industries within Australia (the focus of this paper) and globally need to be carried forward to these emerging water projects. The added benefit of using learnings from CSG and shale gas is that they will enter end of life brine and salt management before many emerging opportunities are implemented, leading to further learnings. Other sources of potential learnings include management of acid mine drainage (AMD) and legacy blow-down water from cooling at power stations.

Methodology

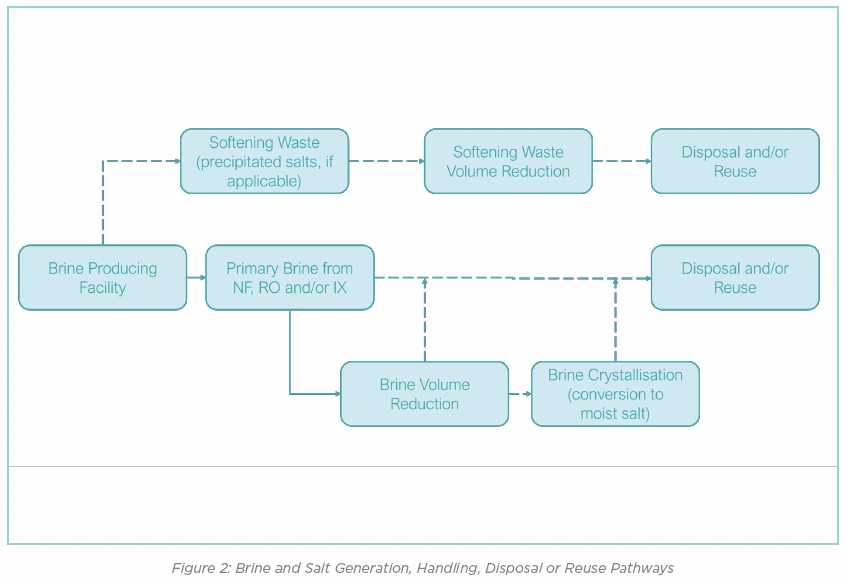

Brine management focuses on linking together brine disposal and/or beneficial salt reuse with the processes of generating the brine, which may include several different unit operations in the water treatment process. Source water chemistry, water treatment process and any brine treatment process each affect the composition, volume and potential stage generation of byproducts. Primary (liquid) brines are generated from ion exchange, nanofiltration and RO processes, and precipitated salts are generated from softening processes. Brines may also be combined with other waste streams which changes the brine composition and complicates brine management. Brine streams may undergo partial treatments with some streams reprocessed or beneficially reused, prior to generation of a “final residual brine” which needs to be managed or disposed of.

A brine management strategy must be customised depending on:

• the process which generates the saline residual(s)

• the overall salinity and concentrations of critical brine components

• a range of external factors including the geographic location, financial and technical resources, opportunities for recovery of valuables, and/or co-location with industries and land uses capable of beneficial brine reuse or use of selective salts.

Figure 2 presents an overview of how different brine and salt streams arise.

Overall approach to brine management

The very first consideration is to assess whether salt removal (and hence creation of a brine) may be avoided. However, this is often not feasible for product water quality targets and the available raw water sources, and leads to the need to develop a brine management strategy.

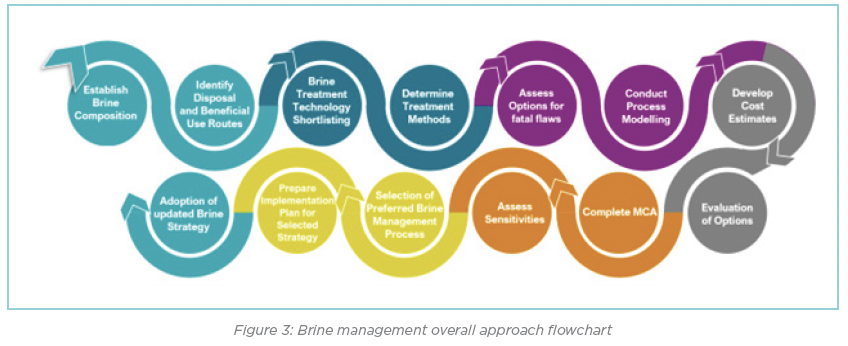

The overall approach to brine management can be broken down into 5 key steps, with Figure 3 depicting a flowchart of the approach:

- Establish a preliminary estimate of the brine composition and quantity, including any separable saline residual or salt precipitate streams. Apart from variability in raw water quality, reagents used in the water treatment process may report to the brine stream, and changes to reagents over time may impact upon variability in brine composition.

- Identify the disposal route options and any potential beneficial reuse opportunities. Consider whether changes to the water treatment process would create more byproduct reuse potential, and whether variability in brine composition would impact upon subsequent options.

- Assess disposal and reuse options for general feasibility.

- Assess the brine treatment technologies available to render the saline residual in a state suitable for each disposal or reuse option.

- Evaluate the available options to determine preferred brine management strategies.

Step 1: Establish brine composition and quantity

For any project, establishing the source water quality and its variability is crucial to consideration of brine management design. For projects, ideally five years of sampling would be available to adequately characterise base water quality and observe changes in seasonality, source locations and if an existing plant, plant performance to act as the key inputs to the design of downstream infrastructure. In addition to the amount of time required to procure adequate raw water quality data, it is important to analyse the relevance of data in terms of whether samples are representative, appropriateness of sample handling, and adequacy of analytical methods including limits of detection. Ideally, sampling and analyses should be completed by NATA-accredited facilities with field-testing of parameters such as pH and dissolved oxygen. Following the collection of data, consideration should be made to the variability of sampling results, key sensitivities in the water chemistry which may affect system selection, key environmental focused parameters and ultimately the development of feed water quality envelope to adopt as a basis for the project.

Step 2: Identifying disposal and beneficial use routes

A brine management strategy is directly inter-related to the water treatment objectives (recovery and quality), and so any change to the water. A brine management strategy is directly inter-related to the water treatment objectives (recovery and quality), and so any change to the water treatment objectives requires a review of the brine management strategy. Brine management may include a combination of disposal and / or beneficial reuse routes. The required technology to convert brine to the required quality is likely to vary for each disposal or reuse option. Therefore, to determine the level of treatment required and which options would be beneficial, the final disposal or reuse routes need to be quantified, so that the required brine treatments can be determined.

When considering potential disposal and beneficial use routes, it is important to consider the consistency of operation of the main process producing the brine. If this process changes in operation throughout the year e.g. doesn’t run for periods of time or ramps up and down in production rate, consideration needs to be given as to how these impacts affect the potential brine disposal route. If a variable brine production rate or operational modes are expected, consideration to simpler disposal routes should be prioritised or reliance on multiple disposal options are required, to increase resilience of salt management.

Potential disposal routes or beneficial reuse include:

- River or ocean discharge (may require long pipeline with suitable containment and ongoing monitoring)

- Irrigation, contingent on plant/crop type and soil characteristics.

- Small volume livestock watering, dependent on salinity and composition.

- Liquid trade waste discharge to sewer (generally needs to be small volume to avoid wastewater treatment works issues).

- Injection into confined geological strata or underground mine voids (challenging in Australia due to the abundance of voids, potential containment issues, nearby aquifers and groundwater contamination. As a general requirement, the injected brine must not worsen the quality of the pre-existing groundwater in that location, and containment must be proven. For virgin geological structures, the receival measures are generally fissured or porous strata, such that high pressures are required to force the brine into available void volume, and the operating pressure will increase over time as void volume decreases).

- Co-disposal with other waste materials, such as mine tailings, power station fly ash or biosolids (note that re-release of salts is always a major constraint for this option)

- Landfill encapsulation after evaporation and/ or crystallisation.

- Brine valorisation, via selective recovery of marketable elements or compounds. A critical aspect of this option is to determine whether the required product quality (purity) will be able to be achieved consistently, and at what cost compared to the market value of the product. Market evaluation needs to consider the pricing impact of adding product to that market.

- Beneficial use as a feed product for materials like road base, and non-load-bearing concretes.

- Feedstock for microalgae production to generate high-value products.

Step 3: Brine treatment / minimisation technologies

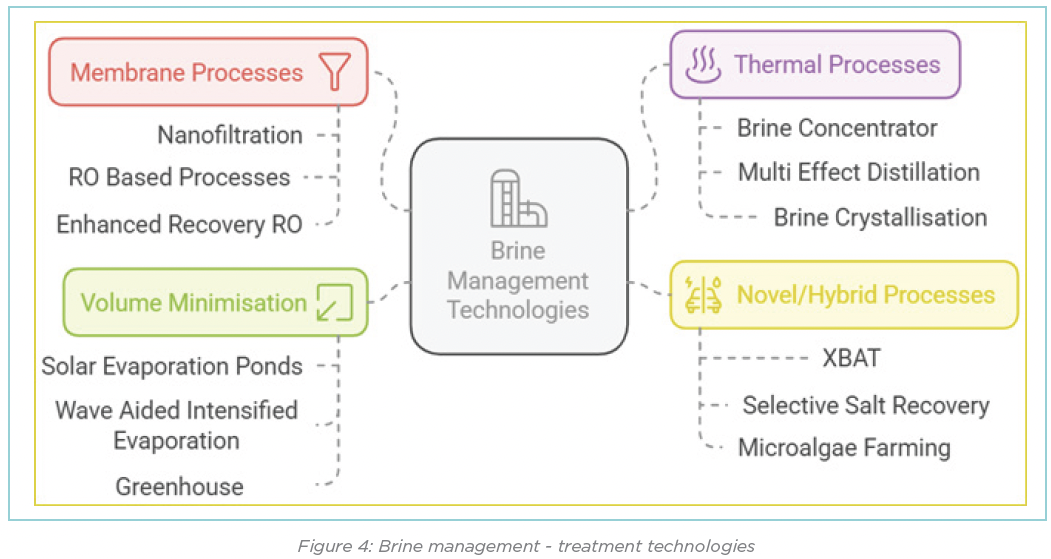

Once the disposal location, quantity and quality of the end product have been confirmed, then investigations into appropriate treatment methods can be undertaken. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. The technologies used for brine treatment can generally be grouped into one of the following four categories, as presented in Figure 4. The list is not exhaustive with many innovative and novel options being developed and tested around the world, of various Technology Readiness Levels (TRL).

Step 4. Determine treatment methods and sizing/ capacity

To inform decisions around brine management strategies, it is necessary to use various desktop-based modelling methods. The preferred method to use is dependent on the treatment process, water quality and detail required. Examples include:

- Water balance modelling to determine overall process residual flows and indicative qualities

- Functional chemistry modelling to understand the effects of temperature, pressure, analyte concentration, pH and chemical dosing - all of which impact upon brine chemistry and options for selective salt recovery

- Process unit modelling to understand the required sizing of various infrastructure components to determine footprint requirements.

Modelling outputs can then be used to inform appropriate equipment sizing, vendor engagement and the development of costing for particular options. Modelling provides confidence for the adoption of options and allows for an understanding of limitations of particular systems, which is crucial to comparison. The modelling allows for multiple scenarios and feed water quality variations to be considered as well as the balance of operational costs or sizing of equipment required to handle potential variations. Modelling also allows for inter-dependencies between parameters to be understood including equilibrium concentrations of chemical species in solution, saturation indices, temperature and pH variations and evaporation and crystallisation effects. These factors are particularly important when looking to stage the order of a treatment strategy. Whilst modelling results allow for increased confidence and determination of system conditions for decision making, results need to be thoroughly reviewed and compared to the general expectations of vendors and users.

Step 5: Evaluate holistically to determine preferred approach

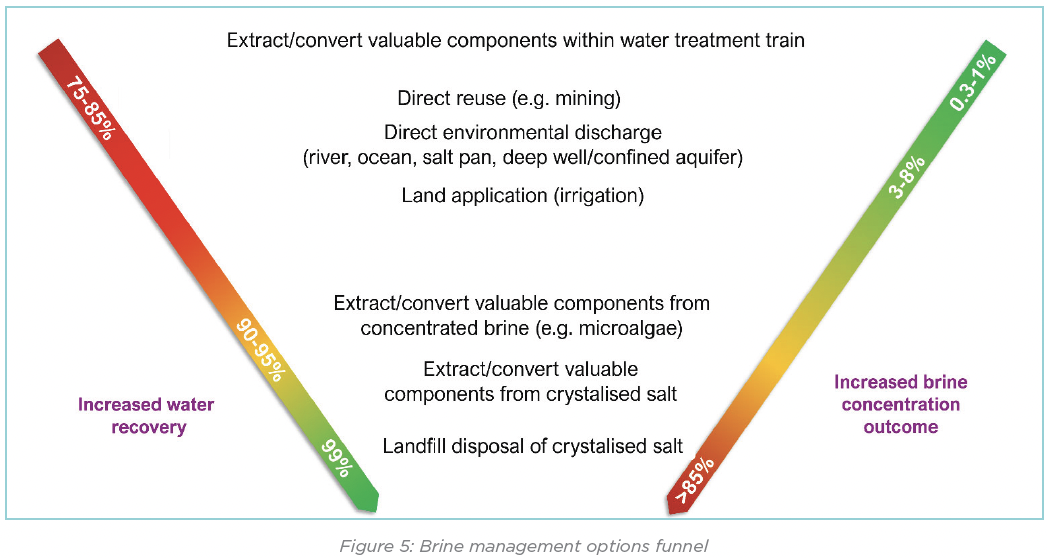

Prior to progressing to a detailed evaluation once options have been identified and preliminary sizing and capacity is determined; it is important to consider the flowchart of decision making which follows the saline waste through potential options. Figure 5 presents the options funnel which should be considered to maximise the opportunities available for brine management, before completing the evaluation of the options.

The intention after completing the preliminary engineering design and considering the options funnel is to holistically evaluate the various concepts developed to determine a preferred method for further development and implementation. This involves completing a multi criteria analysis (MCA) where both financial and non-financial aspects are considered. Criterion is developed and scored with the appropriate weighting assigned to each criterion. Consideration needs to be made to the level of design at the project stage and the potential variability over the project lifecycle of the brine production based on throughput. This will allow options to be assessed using the net present cost (NPC). This will allow comparison on a whole of life approach including consideration to volume effects on maintenance and complexity of options.

This information can then be assessed through the MCA and costing basis incorporating stakeholders with varying backgrounds to set the criteria, weightings and scoring. There is potential when completing the MCA to add other complex methods of evaluation e.g. embodied carbon, greenhouse gases etc however these are project specific and can be complex to quantify between options.

Table 1 below outlines the selection of options, their features and limitations which is used to inform the background information for the various stakeholders completing the MCA analysis. The overall brine management approach needs to utilise available options in order of cost and complexity, leaving as little volume as possible to be subject to the more complex and expensive options.

Discussion

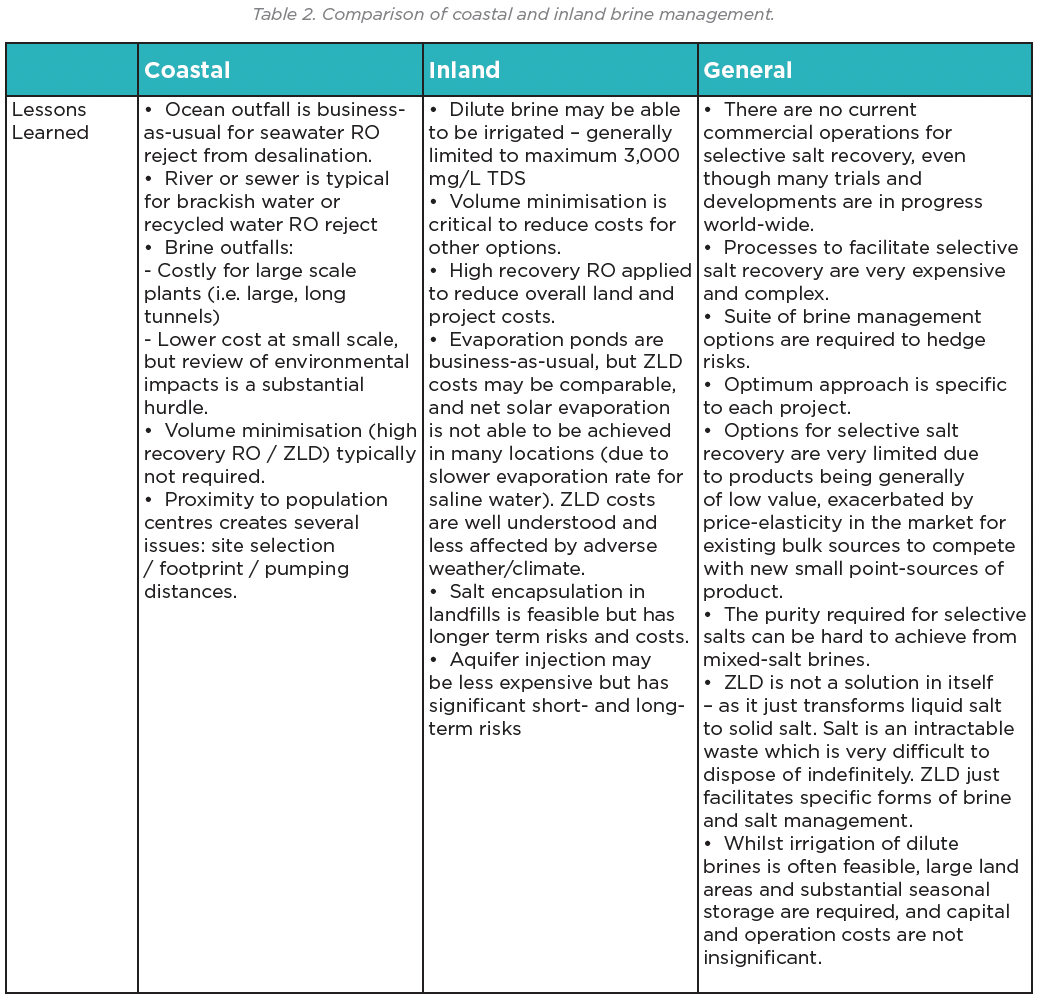

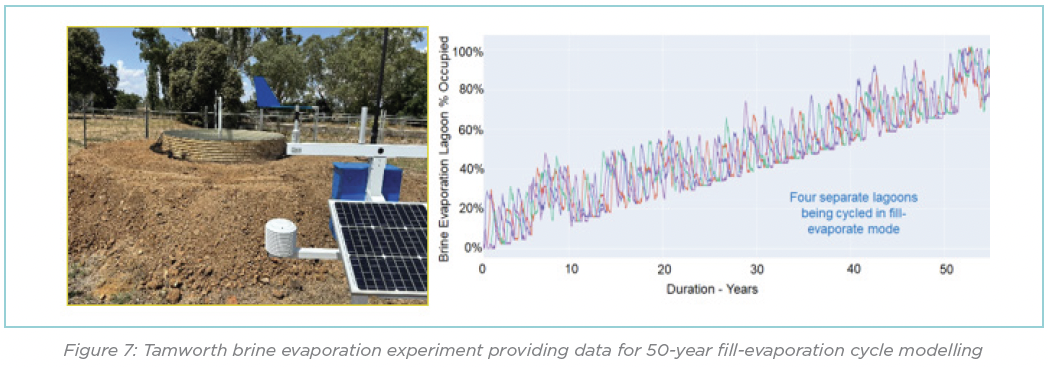

When developing a brine management strategy, coastal and inland brine management schemes each have their own unique challenges affected by geographical location, project scale and brine chemistry. Table 2 presents lessons learned from, and challenges for coastal versus inland brine management.

Irrespective of whether the brine management system is inland or coastal, there is the potential to investigate beneficial reuse applications which should be considered through the development of any strategy. Prior to finalising the strategy, consideration needs to be given to potential beneficial reuse opportunities. Some examples of potential beneficial reuse opportunities include:

• Blending crystallised salt with products such as building products e.g. road base / concrete

• High purity regent recovery such as chlorine, acid and alkalis (Morgante, et al., 2024) (Campione, 2025)

• Component recovery including phosphorus and phosphate for agriculture and industry (Wenten, et al., 2017)

• Use in energy storage/generation - salt batteries (Lakeh, et al., 2020) and saline gradient solar ponds (SGSPs) (Alcaraz, et al., 2018). While there is evidence of SGSPs having commenced operation, it is understood that it is very difficult to maintain the salinity gradient in large ponds due to the impact of mixing caused by wind. Also, a SGSP only uses a bulk volume of brine once, and from there on, only accepts enough dilute brine to maintain level, meaning that SGSPs do not provide an ongoing brine disposal or reuse option.

• Electrodialysis systems (MediSun, 2024)

• Recovery of beneficial metals / compounds from brine – e.g. lithium, gallium, other rare earth metals (Graedel & Elimelech, 2023) (Voutchkov, 2025).

However, with any beneficial reuse opportunity, it is important to consider that any residuals not able to be re-used would be subject to the general brine disposal options to manage the final waste.

Case Studies

To illustrate the application of this brine management approach, one USA-based project is discussed based on published literature, and two Australian-based case studies that the authors have been involved in are presented. These examples are focused on water purification which demonstrates that as demand for these sources increases, so will the reliance on adequate and considered brine management.

El Paso (Texas, USA) Blue Brine

Approximately 10% (100 ML/d) of the municipal water supply for El Paso is supplied via the Kay Bailey Hutchison Desalination Plant, which desalinates groundwater of approximately 13,000 mg/L TDS. Its brine is currently disposed via aquifer injection, but that disposal route is becoming exhausted (Atkinson, 2024).

Over several years, a private brine treatment facility has been constructed and planned to accommodate the brine, and produce caustic soda, magnesium hydroxide, and hydrochloric acid. El Paso Water has entered an agreement with a private supplier to take their brine and purchase back any purified water produced from the brine, (Mendoza-Moyers, 2023). The facility, designed for approximately 13 ML/d input flow, is currently under re-development and re-commissioning by Blue Brine (Slyvia, 2024). The authors have not been able to procure any updated information as to the status of the project, but its viability is understood to be underwritten by local demand for the specific products.

Tamworth (NSW, Australia) Water Purification Facility

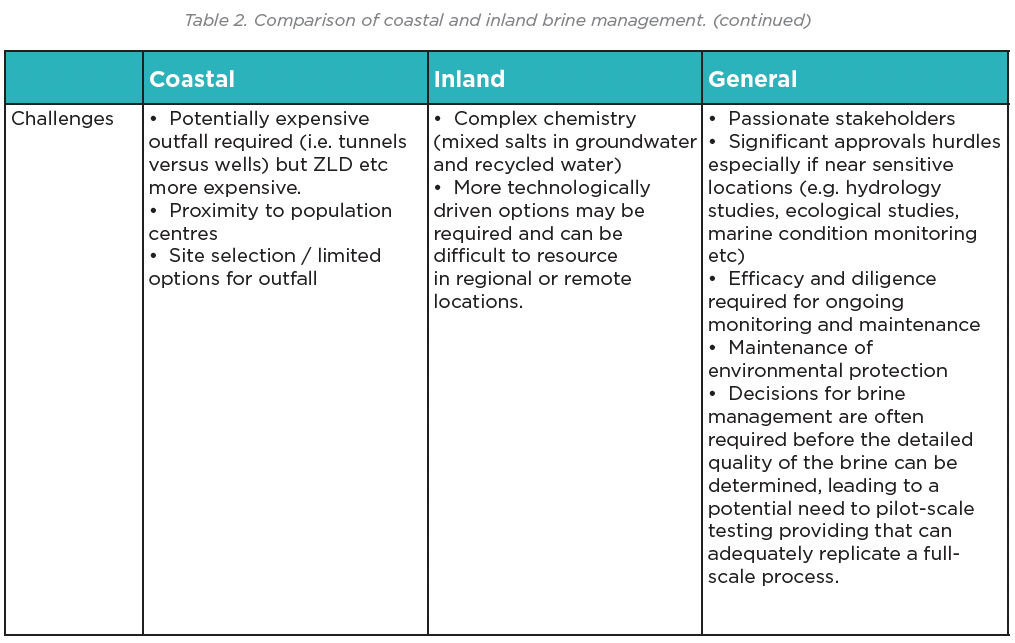

The proposed facility will recycle up to 12 ML/d of secondary-treated liquid trade waste from three abattoirs and a rendering facility, to generate drinking-quality water as a potable water substitute in closed loop recycle to the same industry users. All options for saline residual were considered – and the proposed solution is advanced RO pre-concentration to 5-8% salt followed by solar evaporation for ultimate capping and salt containment.

Assessment of options followed the methodology presented in Figure 3. Tamworth already employs pivot-style irrigation of its treated effluent to produce lucerne. That facility has consumed readily available land and is at the limit of its salinity-handling capacity. Nearby land for irrigation of dilute brine is not available, and the local soil characteristics are not suited to elevated-sodicity irrigation. As commercially proven and available options for extraction of products from the brine are not yet proven at scale and would require extensive piloting and demonstration (beyond the capacity of a regional Council), that option was not progressed. Accumulation of salt was determined to be the only option, and so the assessment relied on balancing cost-benefit, and land availability, for each of advanced RO brine concentration, thermal brine concentration and solar evaporation. Solar evaporation of primary brine was determined to be out of the question due to an excessive land area requirement, and thermal brine concentration consumes 20 to 30 kWh/m3 meaning that the primary brine needed further concentration via advanced RO to reduce its volume. The final stage of treatment was a choice between solar evaporation ponds and thermal concentration. The estimated capital and operation costs for thermal treatment were found to be substantially higher than for solar evaporation ponds, and in this case the final pond sizing was driven by the volume requirement for 50 years of salt accumulation, rather than the rate at which evaporation could occur.

The SGSP concept was considered for Tamworth, but as the evaporation ponds will be very large, the wind-mixing impact was considered to be a very high probable risk, and the lack of ongoing brine consumption failed to address the underlying requirement.

The proposed evaporation and accumulation pond layout (refer Figure 6) specifically allows for adaptive pathways by allowing space provision for possible future treatment scenarios including ZLD, microalgae and/or selective salt recovery.

The proposed evaporation lagoons will operate in a cyclic fill-evaporate sequence, catering for 50 years of salt accumulation and will occupy 37 Ha of land. The lagoon construction cost will be 25 to 30% of the overall project capital.

Bearing in mind the large cost component, it was considered prudent to undertake a brine evaporation experiment at Tamworth to assess actual net evaporation after rainfall, throughout the entire evaporation sequence from 5% salt to moist salt, since the evaporation rate of saline water is known to be slower than for fresh water, declining as the concentration increases. The experiment has been running since December 2023, and it is expected to run for at least two more years to achieve full evaporation. Data (including detailed data from a weather station at the experiment location) from the first year of measurements were used correlate actual evaporation rate with published pan evaporation rate for the corresponding period. That correlation was used to assess fill and evaporation cycles when subjected to the previous 50 years of published weather data, and those outcomes were used to update the lagoon size requirements for the final business case design.

Australian Inland Purified Recycled Water Facility

The referred project is at an early stage of evaluation, and it was recognised that brine management is an issue that could be a showstopper if not considered and catered for at an early stage. The process described in this paper was followed to develop a suitable brine strategy, and that strategy has resulted in planned adoption of a multi-faceted solution which is likely to include:

• precipitated and dewatered salts from intermediate softening process(es) to be co-disposed with biosolids

• some river discharge, subject to flow, dilution and concentration constraints assessed using ANZECC & ARMCANZ (2000) water quality guidelines as amended (brine at approximately 3,000 mg/L TDS)

• a significant portion to woodland irrigation subject to groundwater, soil and vegetation studies (brine at approximately 3,000 mg/L TDS)

• advanced RO concentration of the remainder followed by thermal ZLD processing and resulting salt to landfill.

This strategy adopts the objective of progressively implementing higher-environmental impact, higher energy consumption and higher cost solutions only to the extent needed. For this case, solar evaporation ponds are not feasible even though the ‘headline’ pan evaporation rate is higher than the average rainfall.

Conclusion

Brine management represents a multifaceted challenge that requires comprehensive investigation and planning. While some low-cost and low-complexity options might not cater for all of the brine or salt waste, it is crucial to employ such solutions to the extent possible, to reduce reliance on more complex and costly approaches. Proponents need to understand that brine management will not necessarily involve a single solution.

As desalination and water recycling become increasingly vital due to climate change, growth of population and industries, all increasing competition for water, addressing brine and salt management will gain greater prominence. This is especially important where it may historically have been overlooked for inland applications. Many existing industries, including mining and CSG production, are approaching end-of-life, leading to the urgent need for remediation strategies for brine ponds and other associated decommissioning challenges.

Advancing towards a genuine circular economy and achieving the UN SDGs demands the recovery of salts, metals and minerals where possible. Considerations for brine and salt management must be integral to water supply planning, so that a holistic approach is taken to all aspects. Brine management is not merely a technical problem as it also requires consideration of the social, environmental, and commercial facets. Communities and ecosystems can be directly impacted by brine management activities, necessitating responsible practices.

The development of a brine management strategy following the methodology outlined in this paper:

1. Establish Brine Composition and Quantity

2. Identifying Disposal and Beneficial Use Routes

3. Brine Treatment / Minimisation Technologies

4. Determine Treatment Methods and Sizing/ Capacity

5. Evaluate holistically to determine preferred approach allows for the development of effective brine management strategies which will allow for climate resilient future water supplies for our future communities. The path forward involves innovative solutions that not only address the technical complexities but also align with broader societal values. Collaborative efforts among industry stakeholders, policymakers, and affected communities are essential to develop sustainable and equitable brine management frameworks. By embracing holistic strategies that integrate technological advancements with social conscience, we can effectively tackle the challenges associated with brine management, fostering resource optimisation, environmental stewardship and economic viability.

Nomenclature

|

Definition |

|

|

AMD |

Acid Mine Drainage |

|

BWRO |

Brackish Water Reverse Osmosis |

|

CSG |

Coal Seam Gas |

|

MCA |

Multi Criteria Analysis |

|

NATA |

National Association of Testing Authorities |

|

NPC |

Net Present Cost |

|

PRW |

Purified Recycled Water |

|

RO |

Reverse Osmosis |

|

SGSP |

Saline Gradient Solar Pond |

|

SWRO |

Seawater Reverse Osmosis |

|

TDS |

Total Dissolved Solids |

|

TRL |

Technology Readiness Level |

|

UN SDGs |

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

|

XBAT™ |

Softening and Ion Exchange Based Advanced Treatment (Carollo Engineers, USA) |

|

ZLD |

Zero Liquid Discharge |

References

Alcaraz, A. et al., 2018. Design, construction and operation of the first industrial salinity-gradient solar pond in Europe: An efficieny analysis perspective. Solar Energy, pp. 316-326.

Atkinson, B., 2024. Personal Communication - site visit.

Campione, A. P. D. L. B. G. V. F. C. A. M. G., 2025.

Closed-Loop Value Generation for Desalination Plants: The SUEZ-RESOURSEAS Approach to Brine Valorization. Adelaide, Australian Water Association.

Graedel & Elimelech, 2023. Prospects of Metal Recovery from Wastewater and Brine. Nature Water.

Lakeh, R. B. et al., 2020. Repurposing Reverse Osmosis Concentrate as a Low-Cost Thermal Energy Storage Medium. Journal of Clean Energy Technologies, p. Vol. 8.

Leslie, G., 2010. The role of MBR and MBBR pre-treatment in advanced water recycling. Water Practice & Technology, 5(2).

MediSun, 2024. Inegrating RED Tech. [Online]

Available at: https://www.medisun.energy/#tech

Mendoza-Moyers, D., 2023. Incoming $100 million facility looks to turn brinewaste into water, expand El Paso’s water supply. El Paso Matters, 21 November.

Morgante, C. et al., 2024. Pioneering minimum liquid discharge desalination: A pilot study in Lampedusa Island. Desalination, p. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. desal.2024.117562.

Slyvia, J., 2024. Unlocking Brine. IDRA Global Connections, Spring(June).

Voutchkov, N., 2025. NEOM Paves the Way to Innovation in Brine Valorization, s.l.: ENOWA-NEOM water Innovation Center.

Wenten, G., Ariono, D., Purwasasmita, M. & Khoirudin, 2017. Integrated processes for desalination and salt production: A mini-review. AIP Conference Proceedings, p. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4976929.

The Authors

Brendan Dagg

Brendan Dagg is a Chartered Senior Process Engineer at Beca HunterH2O, specialising in designing and optimising water infrastructure. Entering the water industry in 2018, he has cultivated a robust portfolio of successful projects for clients throughout Australia and the pacific. He is committed to fostering the next generation of engineers and advises final-year chemical and renewable engineering students at the University of Newcastle. He is an active member of professional bodies including being a NSW AWA Branch Member, Chair for the AWA Newcastle Sub-Committee, Deputy Chair of the Newcastle Chemical Branch of Engineers Australia and the 2025 AWA NSW Young Water Professional of the Year.

Dr Bruce Atkinson

Bruce Atkinson is a Senior Principal with Beca HunterH2O, having more than 40 years’ experience as a process engineer, and 27 years’ experience in the Australian water and wastewater industry. He has been involved with recycled water projects, ranging from dual reticulation to potable water substitution and purified recycled water (PRW). He is also routinely involved in the design and procurement of brackish water desalination, mine water and industrial water treatment systems. Bruce maintains a strong focus on leading edge options for managing process residuals, especially brine and chemicals of concern including PFAS.